It has been a quarter of a year since I wrote to you last. Arohamai. It’s a sign though that I’m otherwise flat out. This is a short but significant posting. I want to salute three pou, men who have been significant in my life, and who have passed into the long night; Joe Tuahine Northover; Fr Terry Dibble, and; William “Burma Bill” Maung, and to let you know of changes in my own circumstances.

The koroua Joseph Tuahine Northover died in early April at the age of 84. He was a seemingly fit old fulla, and his sudden death took most of us by surprise, although to be fair these kaumatua carry a huge workload and end up outdoors in all sorts of weather fulfilling their ‘tikanga’ roles. Joe was one of those people you could go to for advice about the sometimes complex world of Maori tikanga and the crossover into tribal politics. He chided me a while back about being too ready to “wave the taiaha” in pursuit of our Waiohiki marae project. I listened respectfully. Joe’s whakapapa includes Ngati Porou, Ngati Hine, and Ngati Kahungunu. He was a member of the Waitangi Tribunal and was the ‘go to’ kaumatua for many Government Departments in the Hawke’s Bay, including the Police.

He was an exemplary practitioner of whaikorero and was a Minister of the Ringatu religion. It was in this area that his skills reached into the realms of the metaphysical. When I first came to the Hawke’s Bay he was a bulldozer driver for the City Council. He’d often be at the old Redcliffe dump pushing piles of rubbish around. Sometimes you’d see a carload or two of Maori gathered around him whilst they asked him to bless a taonga or perform a karakia to relieve illness or spiritual malaise. I was a bit naïve and I asked Taape about it. She simply said “he is a tohunga” and the circumstances of this man with a very ordinary job and a very special set of gifts were left unexplained.

Of course in recent years his important roles had him dressed in classy suits and travelling in equally classy transport. A week before his death we were seated in the airport lounge at Napier. Our flights had been delayed, so we started chatting about local issues including the extensions to the airport runway and the impact on the local hapu. He told me about the times when as a bulldozer driver he refused to work on places that were ‘tapu’. He’d been asked to shift red metal at Otatara and he’d refused, even when threatened with sacking. Similarly he wouldn’t touch the ancient middens at Te Whanganui a Orotu. He recounted to me a story of how in one instance an alternative operator and machine were brought in and how they suffered a litany of accidents and mishaps to the point the work was ceased. Tuahine will be a great loss to our area both in terms of personal character and tribal knowledge, and that was attested to by the huge turnout of tribal leaders from across the nation at his tangi at Omahu marae. Moe mai e te rangatira.

**********

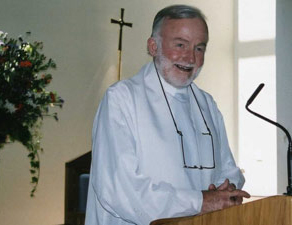

Terence Montague Dibble, was a priest of the Catholic Diocese of Auckland and died later in April at the age of 78. He came from the militant Catholic left, a worker priest ready to take on the modern day Mammon of the aggressive free market, and injustice in any and all of its forms. His shibboleth was “When injustice becomes law, resistance becomes duty”. These were sentiments that appealed to me hugely, especially as an activist and former aspirant to the priesthood. In the late 1970’s Terry was an integral part of the Work Co-operative Movement and our fledgling efforts in establishing alternative education and homework centres amongst the urban Maori and Polynesian youth who were increasingly being eschewed by the education system. But it was his courage and bravery during the 1981 Springbox Tour protests, particularly at Rugby Park in Hamilton, for which most New Zealanders might remember him, for better or worse as the case may be.

He was a staunch supporter of Ngati Whatua in their quest to retain their ancestral lands at Bastion Point, a matter of appreciation underlined by Joe Hawke as he led a haka powhiri as Terry’s tupapaku, covered with a Maori sovereignty flag, was ceremonially brought into St Patrick & Joseph’s Cathedral in Central Auckland. The City’s political establishment, lawyers, judges, politicians, from both Left and Right were there, fittingly, in spades, including his close friend and confidante Mayor Len Brown who spoke movingly about this good and fearless man. The altar and side pews held just about every member of the priesthood in Auckland (an aged phalanx), and Bishop Pat Dunn was supported by the balance of NZ’s Catholic leadership in the celebration of the Requiem Mass. Of course as Pat Snedden was to point out in the panegyric, there was more than a hint of hypocrisy at play within an institution that would laud him in death but give him little practical support in life. In the liturgy the nature of the first song made me smile, and confirmed the status of Te Reo Maori as our country’s diglossic tongue in preference to Latin. Yes, there listed as ‘Waiata’ the old Church Latin of the requiem flowed:

Waitata

Requiem aeternam dona eis, domine,

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Te decet hymnus Deus, in Sion

Et tibi reddeteur votum in Ierusalem.

Exaudi orationem meam;

Ad te omnis caro veniet.

Requiem aeternam dona eis. Domine,

et lux perpetua luceat eis.

**********

I’ve written about ‘Burma’ Bill Maung in these columns before. The old man died in late May at the age of 91, although he had been incapacitated by a debilitating stroke for several years and had lost the power of speech. The last time we enjoyed his company was back in October of last year when he attended the 40th anniversary of the Wellington BP. Even then one could sense that he knew exactly what was going on as the lads lined up to hongi him and pay their respects. For such a keen intellect it must have been seriously frustrating to be trapped in a body without speech. Yet, somehow, Job-like, he endured.

I’m not exactly sure of when I first met Bill. It was probably around 1972, sometime after James K Baxter’s unveiling at Jerusalem.

To a young wide eyed Pakeha like me ‘Burma Bill’ just always seemed to be there. He was an arresting character and imposing figure – his friend Sir Bernard Ferguson described him thus:

“He was six foot in height, and broad and powerful in build; clean shaven with a good jaw and resolute in appearance. During the past fortnight his name had become familiar to us; everybody had spoken of it with respect and I regarded him at first with a certain amount of awe”.

The context for this was post-war Burma. Bill was of mixed English and Burmese heritage, his mother being Burmese. He saw himself and conducted himself as an English gentleman. He adored Mountbatten. Bill had studied and completed a BA at Rangoon University where he met Aung San and joined the Burmese Independence movement (The Thakin Group) led by U Nu, Bill’s mentor and later Burma’s first Prime Minister. Bill was interned by the Japanese during the War. He had never spoken about this to his family. It is a poignant matter because, as I have had it told to me, the Japanese had raped Burmese women and so this period was never referred to or mentioned as a conscious act of respect towards those women. In any case after the War he joined the Burmese Civil Service and quickly rose through the ranks, eventually becoming the Commissioner of the Sagaing division (about the area of the North Island). In 1962 however the military coup changed all of that and by 1967 he was at risk of death at the hands of the military. With Ferguson’s help he emigrated from the home of his birth to New Zealand with his family. And this is where the second phase of his life was lived out, in an entirely different manner, and where he became the political advisor to the Black Power and a friend and mentor to us all.

He could be a contrary old bugger. Once, a group of Treasury appointed analysts were undertaking a review of the Group Employment Liaison Service, of which I was the CEO. Bill had the Te Waka e Manaaki Trust operating out of the former SIS building in Taranaki St. The Treasury analysts had amusingly ‘dressed down’ and were wearing their gardening jeans and so forth for this ‘field visit’. I brought them in to have a chat with Bill and to get some feedback from the frontline. After an introduction and explanation of the purpose of the visit Bill said “Oh, I see. Well of course you are a bloody waste of time. Always talking about what you are going to do rather than doing it. You drive around in a flash car whereas you could walk. Complete waste of time!” Then, having waited for a moment to let this sink in to his audience he turned to the Treasury group. “Now, however, as compared to you useless bureaucrats the man is a marvel, and as incompetent as he is still manages to get things done whereas you achieve absolutely nothing”. He then proceeded to give an in depth lecture on the failed economic policies of successive governments since the early 1970’s.

Bill has at various times described himself as a God fearing anarchist; as a bible carrying Buddhist; as an activist; as a detached community worker. Each has a story of its own.

The God fearingness was derived from his Buddhism which he showed us was a living system rather than a theology, a pattern of social practice rather than rites and rituals. The anarchist arose from his belief that the laws of God overrode the laws of man. He carried a bible and studied it because he said there was a lot of good in it, and we should adopt good regardless of its source. He was an activist because his life was a ceaseless quest for justice and truth. He was a ‘detached community worker’ because to a great degree he was detached from the quest to acquire material possessions and thus the need to be subservient to the wishes of a funder or employer.

Bill would say that he came to this land for peace and quiet. It may have been for him, but it was certainly not the experience of those in the system that he encountered. He would assume authority in any circumstance and would insist on dealing with whoever was in charge. He habitually wore overalls. Once he was at Parliament for a meeting with Muldoon. The Commissioner of Works commented that he thought it was disrespectful and inappropriate for him to meet the PM dressed like that. “I see,” said Bill. “Well if Muldoon wants to see a suit and tie then I’ll buy them for him, but I think he wants to see me”.

Bill held that all trouble is caused by ignorance and therefore our responsibility is to promote education – education as a living science not a meaning. Consistent with that philosophy, having encountered the realities of his new home of New Zealand, and witnessed the rod on the back of Maori he gave up his profession of teaching and took up education. He told us that one problem with New Zealanders is that we have confused Justice with Law and Order. We are fixated with providing the cure rather than with addressing the problem.

Bill said he was comfortable with the Maori way of life as it was compatible with traditional Burman ways in regards to the practice of aroha, the practical demonstration of love. This he told us was where respect or mana arose from, not from station or birthright.

On the street Bill politicized us, raising our consciousness to challenge not only the system by utilizing political processes — “the ballot not the bullet” – but also to challenge our own behaviours. In some notes he wrote about his work at Te Waka e Manaaki, the Black Power marae in Wellington, he said:

“Progress has not been smooth sailing all the way. One is reminded of James K Baxter’s house at Hiruharama. Baxter wrote — “the canoe takes water on board every day of the week. Each time I think it will fill up or capsize . But it has not sunk yet. I think Te Atua is keeping it afloat”

Our policy at Te Waka e Manaaki, Bill said, could well be described by Baxter’s beatitudes spelt out in Jerusalem Daybook:

“Feed the hungry; give drink to the thirsty; give hospitality to strangers; look after the sick; bail people out of jail; visit them in jail and look after them when they come out; console the sad; reprove sinners, but gently brother, gently; forgive what seems harm done to you; put up with difficult people; pray for whatever has life including the spirits of the dead. When these things are done Te Wairua Tapu comes to live in our hearts and doctrinal differences and difficulties disappear like the summer snow”.

William ‘Burma Bill’ Maung on the steps of Parliament

On the Saturday prior to taking him to lie in state at Pipitea marae we drove Bill around his former haunts and for a brief time laid at the steps of Parliament. This was an institution which provided him with much grist to his intellectual mill. When a security guard came out to object we told him to back off or we would leave him there.

William ‘Burma Bill’ Maung at Parliament

At Pipitea he was honoured by Ngati Poneke as friends and whanau gathered around. The Mayor of Wellington was in attendance as were leaders of the City, and leaders from the street. For the Blacks he was a rangatira, a kaumatua, our pakeke.

It was apparent to me that as his time had come, so a new time had come for me also. Bill was down, and it was time for me to step up. My age is upon me and the time was right. After my poroporoaki to Bill I turned to my Wellington Chapter brothers and told them, “kia pakeke ahau” and laid my patch down on the old man’s coffin.

After 39 years my role as a warrior is done. I have new work to do, borne of age, maturity, and wisdom. My focus shifts from the needs of the Wellington Chapter to the needs of the cluster of whanau who make up the Wellington Chapter and the Black Power community at large. I am a Black Power member for life, and so for me the new role of ‘pakeke’ isn’t an excuse to ‘park up’. In fact I intend to increase my efforts in the drive to achieve whanau ora for the tribe of Nga Mokai, and one way to do this will be to go back to first principles and build from a base on the marae. I seek a 21st Century New Zealand community, founded on Maori values but open to and inclusive of the land and world at large. This is to be the next stage of my life.

D’s patch on Bill’s coffin

Accordingly I call upon the spirits of these three men, Northover, Dibble, and Maung, as I call on you all, to guide me and to encourage me in the difficult days and long journey yet to come.

Te Rongo Toa

O oku tipuna

Ka hinga au

Aue!, ka mate au

Ka takoto toa

Tena i karawhuia

Kia piki! He hau taua

Aue hi!

Denis