“Bill Hamilton saw the sea for the first time when he was four years old — and he was delighted. He trapped some sea water in a bottle so he could make the tide work at home. He was disappointed, of course, but Bill Hamilton was to spend a lifetime testing, and then defeating, the tides and currents of man and nature.”

Maurice Shadbolt, ‘The Man Who Rolled Back the Rivers’

Bill Hamilton’s jet-boat revolutionised river and shallow-water navigation. It enabled people to travel for the first time, at high speed – up rivers and waterways all over the world. It was a craft that sped people up the Colorado, Ganges, Amazon, Congo, Mekong, Yangtse and countless other rivers. It opened the door to exploration and the supply of goods and medicines to otherwise inaccessible areas. The jet-boat also became an exciting new form of recreation. It situated Hamilton proudly in the lineage of New Zealand inventors who answered our need for speed.

Back yard laboratory

Back yard laboratory

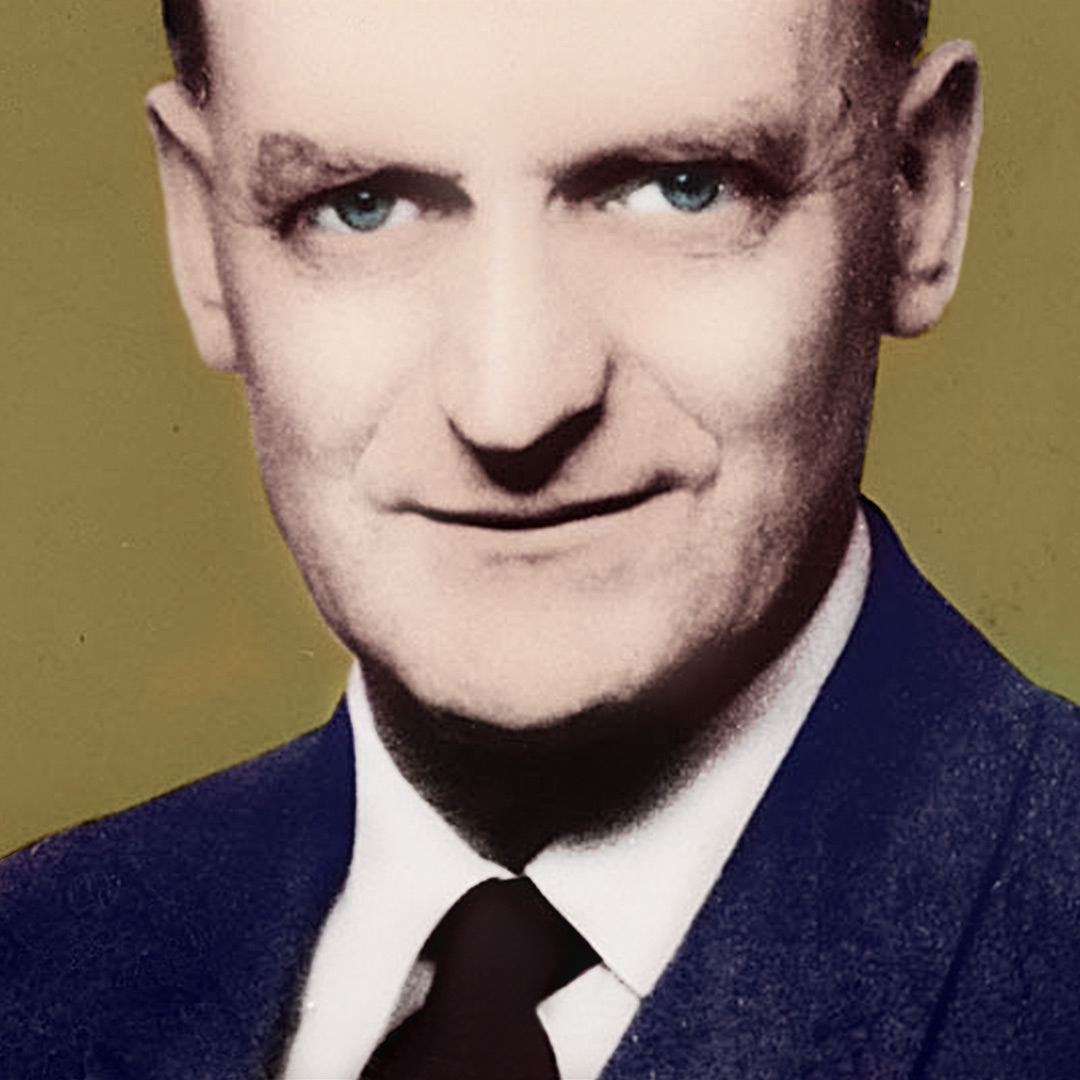

Charles William Feilden Hamilton was born in 1899 on the remote Ashwick Station near Fairlie in South Canterbury. The landscape is carved by mighty rivers; the Waitaki, Clutha and Rakaia, flowing from the Southern Alps. For centuries Maori had used elegant mokihi (canoes made by drying and lashing raupo reeds together) to transport catches of fish and birds downriver and to ferry people across these waterways. As a child Hamilton built rafts and canoes for play, to cavort down the flood-prone Opihi River (a tributary of the Waitaki). To his frustration he required the use of his dog, towing a homemade raft trailer, to get back upstream to start again. Finding a practical solution to avoid the trudge upriver would be the impetus for Hamilton’s waterjet design.

His clear love for inventing solutions to navigate nature started as a young boy in his self-made shed. In 1912, at the age of 13, he constructed a land yacht and subsequently terrified neighbours’ horses as he sped along deserted roads. That same year, handicapped by the lack of electricity in his shed, Hamilton constructed a dam and water wheel to bring electricity to Ashwick Station. This modernization came two years before the government constructed the first operational hydro-electrical station in 1914.

Bill Hamilton as a young boy on a hunting trip, Ashwick Station ca.1912 Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

Bill’s formal education began at Waihi Preparatory School near Temuka, and he was later sent to board at Christ’s College in Christchurch. He found urban life in Christchurch life tiresome, away from the open potential of the alpine rivers but his separation from the Mackenzie country would not last long. In 1916, when his older half-brother Cyril was killed in World War One, Hamilton left school to assist in running Ashwick Station. He went on to purchase Irishman Creek Station in South Canterbury in 1921 for £16 000 with the help of a £9000 loan from his father. The new purchase would become the site of the workshop where he incubated his many inventions. The lack of suitable machinery for developing the farm prompted him to buy his first lathe, and then to build a larger workshop. In 1926, Hamilton erected his own dam to generate electricity for his workshop and farm machinery for developing, and, when this dam was damaged, he built a larger one using an earth moving machine he designed and built for the purpose.

Bill Hamilton’s earth moving machine, Irishman Creek ca.1926. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

During the 1920s Bill became fascinated with the new sport of motor-racing and purchased a Bentley racing car on a trip to England in 1923 and began racing competitively. In early 1924 he returned home to Irishman Creek with his new bride, Peggy Wills, an English girl who shared Bill’s love for the outdoors. Back home, Hamilton won the 50 mile New Zealand Motor Cup in 1925, and went on to claim the Australasian speed record in 1928 (he was the first person in the Southern Hemisphere to officially clock over 100mph). In 1930 he took his Bentley to England for the Brooklands Easter meet where he won all his races – the first driver to do so.

Bill Hamilton after winning the New Zealand Motor Cup, Auckland 1925. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

Design for Life

The Depression years saw Hamilton design and build a myriad of machines for a living. Raw materials were brought into Irishman Creek and engineered into finished products: a shingle loader, several scoops for earthmoving, a hay lift, a water sprinkler, an air compressor, an air conditioner, and others. The scoops were to be a saviour in the tough years as wool prices plummeted, being used the length of New Zealand to carve out airports and roads (they were later manufactured under license in Britain).

In 1939 CWF (Charles William Fielden) Hamilton & Co Ltd, was formed, and Bill’s remote mountain workshop became a factory, manned by shearers, musterers, and farmhands. The company’s first contract was for an airstrip in Twizel. Bill had by now retired from competitive racing, but utilized his Bentley for high speed ‘smoothness’ tests on many of the airstrips he constructed. During World War II the factory produced precision munitions (such as Bren gun firing pins that required very accurate engineering). Maurice Shadbolt writes, “accountants and economists were baffled by this factory risen from nowhere, so far off the beaten track and remote from markets – and by a designer and engineer who had never had an hour’s formal training”.

The workshop at Irishman Creek during the mid 1950s. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

A lack of power supply hindered further development and after World War II, Hamilton opened an engineering business in Christchurch. It thrived, allowing him to concentrate on R&D at Irishman’s Creek. He helped design and build the first rope ski tow in New Zealand, and in 1951 at the age of 52, he revisited his boyhood idea of creating a boat that could travel upriver with ease and would be able to navigate the shallow waters around his Station.

The need for speed

Bill Hamilton at the drawing board, Irishman Creek ca. 1954. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

In 1953, after experimenting with a number of concepts without great success, Hamilton approached Christchurch boat-builder Arnold France to advise on the design. Hamilton’s specifications were for a hull suitable for a river craft and a replacement for the propeller. France suggested a jet unit and loaned Hamilton a US pamphlet on the Hanley Hydro Jet which used a centrifugal water pump system. This waterjet applied Newton’s Third Law of Motion: for every action there is an opposite and equal reaction. Throwing water out backwards creates an opposite reaction that drives the boat forward. Hamilton replicated the system and put it into his first jet boat, a 3.5 metre craft fitted with a centrifugal pump and powered by a Ford 10 engine. Water was drawn in under the hull and expelled out a leg in the bottom of the boat. Despite his best efforts, however, the boat was only capable of an unspectacular 17kph (barely faster than a river current). In addition to this, because the leg extended below the hull it was prone to damage in the shallow rivers.

So Hamilton and his team reworked the original design to expel the jetstream out the transom (stern) of the boat above the water line, a modification that saw the top speed jump to 27kph. The design eliminated protrusions below the hull exposed to damage. Conjecture posits that the idea came from a high-pressure fire hose (in Kiwiana myth this has become a high pressure milking hose). Whatever, it was the genesis of the modern waterjet propulsion system. Hamilton sold his first boat in 1955 to a friend.

A further breakthrough came in 1956 when George Davison, a Canterbury University Engineering graduate working with Hamilton, suggested a 2-stage axial-flow unit. Others had tried using an axial-flow device for propulsion (rather than a radial pump or the traditional screw propeller), but Hamilton succeeded in finding a suitable application, where its advantages (shallow draught and high manoeuvrability) outweighed its disadvantages (lower efficiency and higher expense) compared to standard propeller power.

Bill on the Ohau River – Easter 1954. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

Shifting to the axial flow jet (which generally means high volume and low velocity) meant Hamilton could pump a greater amount of water than with the centrifugal pump (low volume, high velocity). A low pressure/high velocity jetstream is an important part of a fast and efficient waterjet propulsion system. To increase the velocity of the water, and thus increase boat speed, they incorporated a series of impellers and stator veins (which straighten out water flow behind each impeller) and added a narrowing of the outlet nozzle. As a fluid passes through a tube that narrows, the velocity of the fluid increases and the pressure decreases (Bernoulli’s Principle). The result was that the waterjet unit could now pump a high volume of water and expel it at very high speed – meaning it could now be used successfully on bigger and heavier high-speed vessels.

The incorporation of the 2-stage axial-flow system led to the production of the “Chinook” in 1956, the first commercially viable jet unit. After further modifications and the addition of a 3-stage unit, the jet was able to reach speeds of up to 80kph. Steering was controlled by swivelling the outward flow. Hamilton finally had the craft he dreamed of: a boat able to swiftly manoeuvre past jutting rocks, and forge upstream through malevolent currents. Because there were no protrusions below the hull, the boat could operate in only centimeters of water, perfect for the stony, braided, southern riverbeds.

1956 – Chinook Unit. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

The Right Stuff: Proof of concept up the Colorado

In 1960 the go-against-the-flow innovation of the Hamilton Jet proved itself when it became the first vessel (a boat called Kiwi) to travel up a 160km section of the Colorado River that flowed through the Grand Canyon. Bill had broken his arm in a boating accident, so his son Jon was at the helm. It was a nine day current-bashing marathon that saw the Hamilton Jet negotiate all obstacles, including the mighty Vulcan Rapid. Four boats made it up the Colorado River in 1960, all powered by Hamilton waterjets.

After this spectacular demonstration other rivers were successfully navigated and the invention was embraced across the planet. The uses of the jetboat were manifold: fishing, oceanic research, tourist travel, fire-fighting, taking geologists into the hinterland of New Guinea or scientists and missionaries up the Amazon, supplying remote Pacific Islands or aiding food relief in India. His modest explanation for how he did it? “By using common sense. By keeping an open mind.” He famously attributed his success to having such a “grand team of chaps” working with him. A grand team he had, but it was Hamilton’s design brilliance, coupled with his ability to engage others in his original vision that brought the Hamilton Jet to fruition.

World-wide demand for the jets steadily increased throughout the 1960s and 1970s to the point that manufacturers in the US, Canada and Britain were contracted to produce Hamilton waterjets under license. The economic conditions of the late 1970s and early 1980s led the company to phase out its general engineering business in order to concentrate solely on the more profitable production of waterjet units for export. Hamilton Jet became the main division of the company with the mandate of building a wider global distribution network for the jets. Branch offices were opened to assist distributors in America and Europe (Asian distributors are supported directly from the NZ factory) and to market and co-ordinate distribution of the company’s larger and more technical HM Series waterjets. As this strategy began to prove successful, factory capacity and staff levels were expanded considerably to meet the growing demand.

Jon Hamilton going through Vulcan Rapid, Colorado River, USA, 1960. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

Though other versions of the marine jet have been developed, the Hamilton Jet still commands a large share of the international market; CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd is a multi-million dollar exporter and the factory employs over 200 people. An estimated 35,000 jet units have been produced by the factory, and since the 1960s, over 2200 boats.

Through the company’s international expansion, Bill Hamilton’s family have remained closely associated with its operations. Bill’s son Jon has been actively involved with the Hamilton Jet. After conquering Colorado he went on to lead the Ocean to Sky trip up the Ganges with Sir Edmund Hillary in 1977. Jon’s son Michael (Bill’s grandson) is currently chairman of the CWF Hamilton board and is also a full-time waterjet designer at the company. Bill’s nephew, gliding legend and world record breaker Dick Georgeson, has been managing director of CWF Hamilton.

Bill Hamilton receiving his knighthood, 1974. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

The water jet is the preferred choice for the efficient propulsion of a wide range of high speed work and patrol boats, fast passenger ferries, crew boats, fire boats, fishing vessels and landing barges. Hamilton jets move more people in Manhattan than any other ferries in New York. The Shotover Jet is synonymous with Queenstown as the world’s ‘adventure capital’, and a staple feature of advertisements selling Aotearoa-New Zealand to overseas visitors.

The gut-wrenching high speed donut, initiated moments before imminent collision with the rocks edging the Shotover, is known as the ‘Hamilton Turn’. It was developed as an emergency stop, but now enables thrill seekers to safely experience the exhilaration of speed. Legend has it that when demonstrating the jet to potential customers, Hamilton used to drive directly at a dock, turning calmly only at the final second (Bond in a Swandri?). The turn was testament to the Jet’s extreme manoeuvrabilty.

A sharp corner at high speed on the Shotover River, Queenstown. Image courtesy of the Shotover Jet

In 1961 Bill Hamilton was awarded the Order of the British Empire and in 1974 he was knighted Sir William Hamilton for “valuable services to manufacturing”. He died at his home in Halswell, Christchurch in 1978 aged 79 and is buried at Burke’s Pass Cemetery between Fairlie and Lake Tekapo. Bill Hamilton was inducted into the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame in 1990, and the New Zealand Business Hall of Fame in 2004.

River King

It was from the glacial veins running from the spine of the Southern Alps, that Bill Hamilton drew his inspiration. He was saddened in later life by the destruction of the land and waterways around Irishman Creek for hydro-electric construction. He accepted the construction as inevitable (his company was closely involved in engineering for the schemes). But these were routes he knew like lines on his palm, and he advocated open-access to the waterways (access that his invention enabled in many instances) and their preservation for the future.

Hamilton loved speed. The free flowing Mackenzie Country rivers were his pulse and challenge. As a four year old he discovered he couldn’t trap the tide in a glass jar, but that didn’t stop him trying to take on the currents; studying, testing, designing solutions that harmonised the natural with the industrial. From his homegrown jet propulsion laboratory on the Waitaki and its tributaries, Bill Hamilton brought the jet age to the water, then took it to the world.

Bill Hamilton at the helm, ca. 1955. Image courtesy of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks and appreciation to Tony Kean of CWF Hamilton & Co Ltd for his assistance in the preparation of this story.

References:

Web:

Visit the Hamilton Jet corporate website

See the “Hamilton turn” in action and view the inner workings of the Jet on the Queenstown Shotover Jet site

Twin Rivers Jet corporate site

Bill Hamilton in the New Zealand Business Hall of Fame

Books:

Bloxham, Les & Anne Stark. The Jet Boat – The Making of a New Zealand Legend, A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1983.

Hamilton, Peggy. Wild Irishman: The Story of Bill Hamilton. Reed, 1969.

Kean, Tony. The Ballad of Bill Hamilton. Spiderweb Publishing, 2002.

Shadbolt, Maurice. “Bill Hamilton”, Love and Legend – Some 20th Century New Zealanders“. Hodder and Stoughton, 1976.

Film:

Against the Flow – the Hamilton Jet Tale

Produced by Black Magic Media: 2004.

I have a DVD copied off of a 16 mm movie made by a professional photographer of a trip up the cataract canyon and that 1962 or 1964. It was also done with a jet boat two Ford 428 cu in³ engine inboard motors.

Later on in 1962 or 64 another fellow went up the cataract canyon it a jet boat with two inboard motors and two jet powered. It is documented on 16 mm film I have copies on DVDs. Charlie

Emeritus Professor Frank Henderson 1921-2006 Emeritus Professor Frank Henderson has died at the age of 84. Professor Henderson graduated with a BE (Civil) from the then Canterbury University College in 1943 and was top engineering student in New Zealand that year. He worked in the Dominion Physical Laboratories of the Department of Scienti c and Industrial Research before joining the staff at Canterbury in 1952. In 1964 he was made a full professor and deputy head of department. Professor Henderson played a leading role in establishing the uids laboratory at Canterbury and his uid mechanics expertise led to the rst axial ow jet boat. He was also instrumental in purchasing the rst computer for the University. In 1968 he took up the position of head of the Civil Engineering Department at the University of Newcastle, NSW, and retired from that university in 1983. Geoff Henderson said a generation of students and colleagues took inspiration from his father’s outstanding grasp of, and pedagogical ability with, the mathematics of physical phenomena. “In the post-war era, he was a leading light in making the Canterbury and Newcastle schools of engineering respected international participants in a ‘brave new world’ which demanded a much more mathematically sophisticated approach to engineering.” Professor Henderson is survived by his wife, Jean, four children and nine grandchildren.

I had the good fortune to work under Bill Hamilton and Jon Hamilton fro 1969 to 1972 at CWF Hamilton and co, as engineer in the Research and development dept. He was one of the finest persons I have met in my life and and was strongly influenced by his philosophy of work and knowledge. Jon his son was also influenced by him, and practiced his doctrine.

Hi, Regarding the Bill Hamilton article. It’s good to acknowledge the jet boat engine as a significant development in NZ history, but if you read `The Jet Boat - The Making of a New Zealand Legend' you will see that the idea to make the pump an axial flow configuration came from Professor Frank Henderson, a Professor in Civil Engineering at Canterbury University at the time. Although George Davidson had a great influence on the fruition of the project, I'd like to introduce another contributor to the success of the jet boat engine. Thank you. JP