At a unique junction where the means of industrial production met a burgeoning consumer culture, New Zealander Joseph (Jo) Sinel recognized the need for new paradigm definition. He made use of a new term to reflect the age and his vocation. It was 1919 and the term was ‘Industrial Design’. It was a nifty neologism that captured how technology and art came together to create designs for life.

“Right In Your Eye And In Your Eye Right”

According to the Industrial Designers Society of America’s (IDSA) official definition, industrial design is “the professional service of creating and developing concepts and specifications that optimize the function, value and appearance of products and systems for the mutual benefit of both user and manufacturer”. As a discipline industrial design is now an integral part of a product’s capitalist arc – from idea, to marketplace, to use – and it was Sinel who had the edge perspicacity to define the distinct role of the industrial designer within the clogs and bits of the industrial machine. An industrial designer’s job was, as Sinel memorably defined it, to ensure that an object was, “right in your eye and in your eye right”. In the Industrial Design Society of America’s Century Review Jo Sinel is listed alongside Mies van der Rohe, Charles Eames, Buckminster Fuller, and Walter Gropius in their Parthenon of influence.

Early work in Auckland. Top: Sinel’s trade card in Art Nouveau style; and below: a calendar he designed for Wilson & Horton. Courtesy of Gifford Jackson and ProDesign.

Born in Auckland in 1889, Jo Sinel was one of a family of ten. His father was from the Channel Island of Jersey and ran a stevedoring operation in Auckland. Sinel attended the Elam School of Art and began his career in the art department of Wilson & Horton Lithographers. There he apprenticed as a lithographic artist at the New Zealand Herald from 1904 to 1909, studying under Harry Wallace. On a typical OE trajectory he went to Australia (where he roughed it in the outback for several months), then to England where he worked in Liverpool for lithographers Hudson, Scott and Sons, Ltd. and the prestigious Carlton Studios in London, gaining commercial experience in Europe’s largest art studio. He later worked for C. F. Higham Ltd, handling such clients as Goodrich Tyres and British Government War Loans.

On The Road

Sinel returned to New Zealand and Australia to work as a freelance designer. In 1918, travelling as a wartime merchant seaman, he immigrated to San Francisco. He found work in an advertising agency, but true to peripatetic form he quit and decamped to the High Sierras where he built a log cabin on the shore of Lake Susie with an artist friend Maurice Delmud. He returned to San Francisco to find several job offers waiting for him. His choice was a position creating promotional graphics at First National Pictures in New York, the movie company with which Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin were associated.

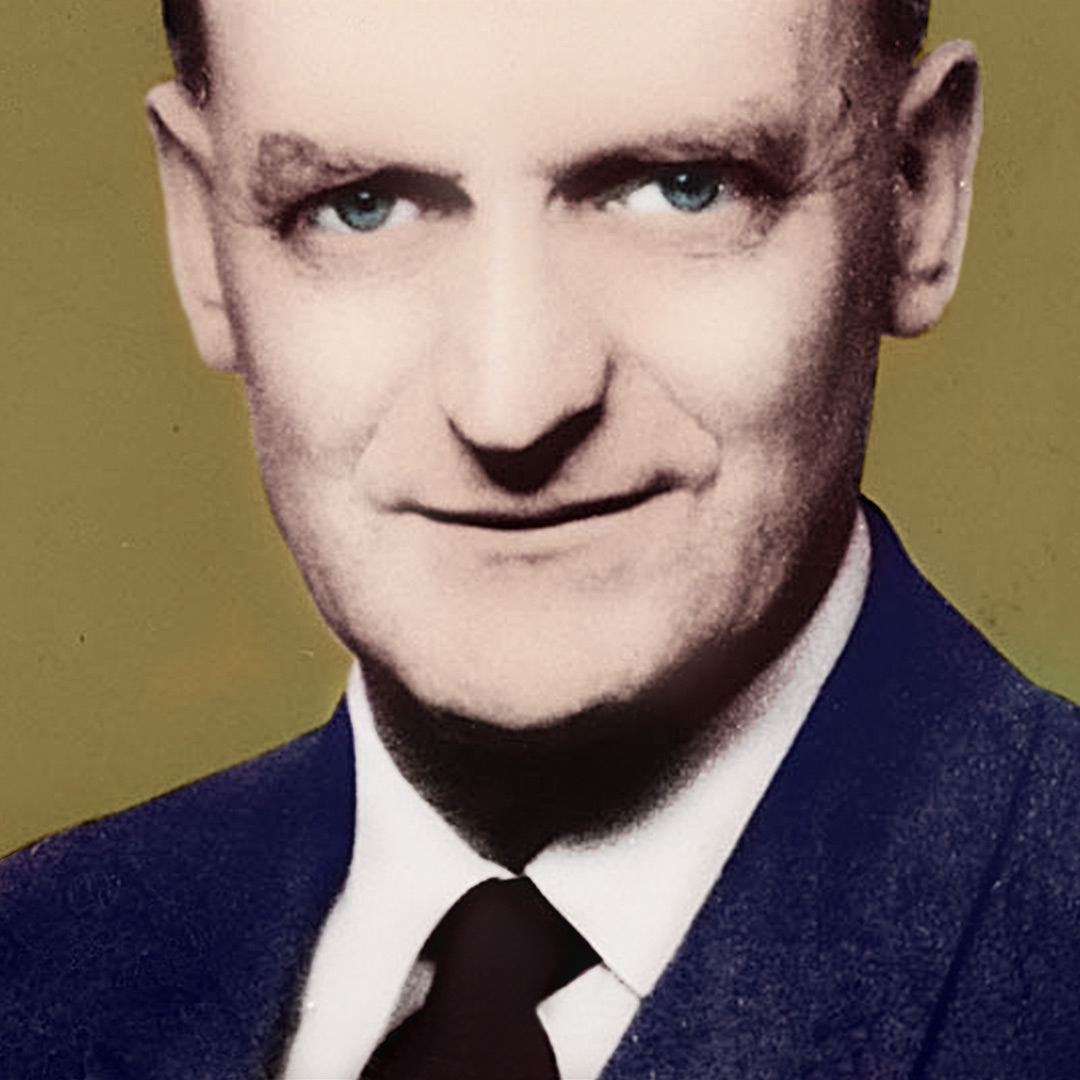

Sinel as a young man in America. Courtesy of Gifford Jackson and ProDesign.

Sinel became fascinated by the automobile and, in an era before most of America was even paved for driving, he set off on the road across the States with advertising graphics for the company’s movies painted on the car’s sides. Thus adorned, he was often photographed on arrival in towns and a front-page feature in local newspapers. This early example of ambient advertising was evidence of the flair for self-promotion Sinel would demonstrate throughout his career.

Arriving finally in San Francisco he worked for several advertising agencies, including Foster & Kleiser (alongside other prominent names in the early history of modern design), specializing in outdoor advertising. He also began teaching at the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) in the early 1920s – an association that would be life-long. But soon, his wanderlust resurfaced: he was off to Montreal and then New York again, where he began to freelance.

Vocation Defined

It was during this period that he popularized the term ‘industrial design’. In the US in 1919 he used the term in reference to drawings of industrial objects used in ads, and in 1920 he stamped the title ‘industrial designer’ on his letterhead. His business card by-line read: “Jo Sinel. Design for Industry, Products, Packages, Displays, Graphic Arts. Sutter Street, San Francisco.”

Sinel did not invent the correspondence of art and technology that industrial design represented. But he did tag a term to a flourishing movement in America. That movement would shape and expand in new directions from where efforts in Britain (beginning in 18th Century with the industrial revolution) and Germany (the Deutscher Werkbund, ended by WWI, and the famous Bauhaus design school, closed by the Nazis) left off. The blossoming of American industrial design in this period, unlike the largely theory-driven Bauhaus movement, was compelled by industry.

Still freelancing and looking for work, Sinel approached “in fear and trepidation” the highest paid art director in the US, Mylon Perley. Perley, impressed with Sinel’s portfolio, introduced him to the Lennen Mitchell advertising agency in New York. He was employed as a graphic artist, but was subsequently asked to also design three-dimensional products for clients, many of them in art deco style. In the seminal article on Sinel, designer Gifford Jackson writes,

“This was 1923, and the designs Jo did represented, I believe, the first steps in America towards industrial design as we know it today.” Sinel remarked later that from years of having to scrape for work, commissions now begun pouring in for 3D product designs. As another pioneer, Walter Dorwin Teague said, “What had been a mere ferment became a high-grade fever.”

Design For Life

Among the first of many products to be designed over his prolific career were scales for Peerless and the International Ticket Scale Corporation (magnificently art deco, they were crafted with motifs suggesting the then ultra-modern skyscraper); the Acousticon and Sonotone hearing aids; Remington typewriters (“the first of the good-looking typewriters”); and calculators for Marchant. Douglas Lloyd Jenkins writes that the Scale “is now considered one of the key works of American design.” Sinel also designed a short-lived automobile called the Newton, which made “futurist designer” Marc Newson’s cross-disciplinary foray for Ford, the O21C concept vehicle, look distinctly 20th Century.

The International Ticket Scale – one of Sinel’s most famous designs.c. 1927

the poster used to advertise the sleek new weighing machine. Courtesy of Gifford Jackson and Designscape. Image supplied by the Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.

Design offices sprang up everywhere. Most were not geared solely towards product design, but embraced a multi-disciplinary approach, creating everything from interiors to graphics. They took their inspiration from the “jazz-modern” motifs and “glamour” silhouettes of Art Deco and the developing rationalism of modernism.

Sinel’s famous Marchant calculator. Top: the original wooden industrial design model of the calculator, photographed by Leo Holub, who worked with Sinel before WWII; and below: the finished product. Photographer Mark Glusker. Both images reproduced courtesy of Mark Glusker.

Birth Of A Salesman

Clients and engineers were initially sceptical about Sinel’s and other early industrial designers’ pioneering prototypes. Sinel needed to develop innovative PR solutions to get his products made, including educating himself about engineering requirements, so as not to be swayed by objections that his designs would be too difficult to produce. Recognising the persuasive value of presentations he became a creative salesperson. He developed a practice of only working with single contacts and promoted his ideas through models and drawings. His simple but effective model for the International Ticket Scale was constructed out of Del Monte fruit crates. It earned him $10,000 and a 25 year royalty deal.

Packaged by Sinel: a Heidelberg Beer bottle (1954); and Alta Tea carton (1947). Courtesy of Gifford Jackson and ProDesign.

Sinel set off from Auckland and walked into the concrete jungle of Madison Ave, but he knew what he was worth, putting a high value on his work and getting what he asked for. One agency directed him $54,000 of work in a single year. His promotional presentations were so effective that he was hired by advertising agencies to help win accounts, at $20-30,000 a show.

Sinel’s graphic design continued to flourish alongside his work on products. In a 1934 Fortune magazine his package designs were featured in a full-page colour spread. His packaging for coffee and cocoa, beer and wine bottles, and other containers still looks sharp 70 years later.

Font Of Wisdom

Sinel produced work for fifty-five advertising agencies during his career, and his client list reads like a Who’s Who of the American corporate world. In the 1940s he returned to the CalArts and later in life he was made an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts. He taught at a number of other design schools, including the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and Chouinard in LA, where he introduced industrial design courses. He was an inspirational teacher at a time when design appeared to be on the cusp of a golden age: the flamboyant American Modern age of electrolux, the Chrysler Building, and art deco. As an apprentice of Sinel’s, photographer Leo Holub, remembers:

“I was in product design, yes. And it was enjoyable. It shook me up and it seemed like the great day for design was coming. There was the magazine from Germany called Gebrauchsgraphik. I was listening to Jo Sinel and I thought pretty soon everything would be fine design. Well, it never happened, as you can look around now and see. Just pre-war [WWII] times there was the sense of good design happening. But it got buried by the kind of thing that’s happening to the general chaos in the visual world.”

Sinel was an outspoken advocate of good design as a solution to increasing ‘visual pollution’. He had what Gifford Jackson describes as a “missionary zeal in espousing the cause of better design.” He was a frontrunner for better-living-through-design initiatives such as 21st Century designer, Bruce Mau’s, Massive Change project. As Mau, channeling Sinel, states:

“… the power of design to transform and affect every aspect of daily life is gaining widespread public awareness. No longer associated simply with objects and appearances, design is increasingly understood in a much wider sense as the human capacity to plan and produce desired outcomes.”

Mixed Media Maestro

Joseph Sinel was one of the 14 founders of the Society of Industrial Designers in 1944, and later, a member of IDSA. He published several books on lettering and trademarks and designed several hundred trademarks for businesses, publishers, institutions and individuals including The Art Institute of Chicago, Doubleday Doran, The Archaeological Institute and Hoffman Ginger Ale. His 1924 book, A Book of American Trademarks and Devices, laid out basic rules of corporate identity and was illustrated with over 300 trademarks he had designed. It was a prescient textbook for what in today’s virulent corporate lingo would be called ‘brand planning’ or ‘image-making’.

- Images from Sinel’s Book of American Trade-Marks. Top: the book cover; and below, his trademarks designed for the Petri Wine Company; the Crime Club; and a symbol for the Archaeological Institute of America. Courtesy of Gifford Jackson and Designscape. Image supplied by the Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.

A mixed-media maestro, Sinel also excelled in the design of publications, magazines (doing covers for several prominent titles), books (including a monograph for his photographer friend Ansel Adams), catalogues and reports. And he also worked in interiors, designing a New York display room for the J Walter Thompson advertising agency, a promotional exhibit on Australia, and an exhibit on the Southern Pacific Railroad for the Golden Gate International exhibition.

Over his career Sinel won many design awards: he was the recipient of the Art Directors’ Medal for Distinguished Advertising Design, The All-America Packaging Award and the National Alliance of Art & Industry Award for Excellence in Product Design. Examples of his work are held in significant design collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Hippie in a Rolls Royce

Gifford Jackson writes that Sinel “was a character who lived his life on his terms with style. Almost all who knew him had tall tales to tell about his exploits. One writer even suggested he could be called the first hippie […] he was certainly colourful … tough, egotistical, argumentative and stubborn, but with many endearing traits. I’m sure Jo got away with murder on many occasions because his talent commanded such respect.” For eleven years Sinel was married to the concert pianist, Genevieve Blue. Douglas Lloyd Jenkins adds that “although most of Sinel’s career took place offshore, unlike many expatriate designers of the 1920s and 1930s he somehow retained many Kiwi characteristics and should he be alive today would have revelled in the Kiwi design invitations that surround outdoor pursuit and adventure tourism.”

The inscription on the 6-ft tall standing scales he designed for the International Ticket Scale Corporation read ‘STEP/ ON/ IT’. Sinel was a person whose life and career was driven by that imperative. He loved fast cars, owning two Rolls Royces and a Bentley, but drove automobiles in the ready Aotearoa style as well, cruising in caravans across much of America and along the edge on two tours home to New Zealand. When he died in 1975, he returned to his place of birth in spirit at least – his ashes were scattered at Kerikeri, on one of his family’s properties.

Sinel in his eighties in the early 1970s. Courtesy of Gifford Jackson and Designscape. Image supplied by the Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.

The Legacy

Sinel’s contemporary, the visionary R. Buckminster Fuller, remarked on his own design process: “When I am working on a problem I never think about beauty. I only think about how to solve the problem. But when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong”. Sinel had simplified Fuller’s best practice mantra to “right in your eye and in your eye right”. His legacy as an innovator and great expatriot designer stands in posterity as inspiration and stellar historical precedent for aspiring New Zealand designers. Jo Sinel: disciplined bohemian, strikingly modern, industrial design neologist, passionate teacher and advocate for good design. A blueprint from the edge.

References

Print:

Much of the factual information in this profile is from Gifford Jackson’s indispensable essay on Sinel, “Right in your eye and in your eye right”, first published in Designscape no. 88, February 1977, and republished in ProDesign, April/September 2003.

We are grateful to Gifford Jackson for helping us at the later stages of preparing this story, and in particular for his help in sourcing images.

Jenkins, Douglas Lloyd (2006), 40 Legends Of New Zealand Design, Godwit.

Web Sources:

[Accessed September 2006]

Further information is available online at the Industrial Design Society of America page on Sinel. Search at: http://www.idsa.org/

Short bio on Sinel and his role in the history of American graphic design, http://www.drleslie.com/Contributors/sinel.shtml

Other Web Resources:

Michael Smythe discusses Sinel here as one of NZ’s many creative expats:

http://www.betterbydesign.org.nz/readingandlinks/features

/thecreativecontinuum/chapter3/

For the catalogue of the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition, “American Modern, 1925-1940: Design for a New Age”, that featured Sinel’s scales:

http://www.metmuseum.org/special/americanmodern/

american_more.htm

For further discussion of Sinel’s scales see: http://dallasmuseumofart.org/Dallas_Museum_of_Art/

View/Collections/Decorative_Arts/ID_011035

Mark Glusker’s site has cool material on mechanical calculators, including Sinel’s Marchant. http://www.mortati.com/glusker/

P22 Sinel Typeface, a font based on an alphabet drawn up in the late 1920s by Sinel. Courtesy Identifont. http://ww.p22.com/products/freefont.html

My father, a friend and contemporary of Mr. Sinel, was a SF Industrial designer and artist. Cornelius Cogswell Sampson sculpted a bust of Mr. Sinel which I saved from my father’s estate. I also own a small watercolor of a New Mexico landscape that Sinel painted. I would like to gift the bust to the descendants of the Sinel family, or to a collection of his work. I remember that my dad and he were friends. After my mother married my father in 1936 in SanFrancisco, she tried to discourage Dad’s Bohemion pals, like Joe. It didn’t work.

I remember my mother has one of these photos in her house the original. And reading about a joseph really makes you proud of your great relatives I never knew him personally he's was far before my time as I'm 24 but I look identical to him in comparison with is how I was told about him by my mother. She made me sit and compared the photos and I was a spittig image as the same for my older brother. Would be great to get in contact with you sally as it looks like were related

My father was a friend of Jo Sinel in the San Francisco Bay Area. I just came across an unfinished book of logos titled "A new approach to an old problem; The Trade-Mark" by Jo Sinel. Proposed copyright 1959. There are several hand drawn images by Jo along with images that were pasted into pages with proposed text placements. Very interesting grouping of logos with a section, "Marks designed in collaboration with Carl Noell"" There are also two wonderful color photos of Jo taken in Oakland in the mid-1970's along with a note to my father about the unfinished book. Jo is pictured in a full vested suite with fedor hat and a wooden cane. He looks very striking!! If anyone is interested to see or have these documents, please let me know.

Great article! I devoted six pages to Jo Sinel in my book 'New Zealand by Design: a history of New Zealand product design' (Random House 2011). Gifford Jackson was a primary source but I also purchased a copy of the June 1936 copy of PM [Production Managers] magazine on Ebay which includes a 13 Page article 'Joseph Sinel - artist to industry' by Percy Seitlin.

I am researching my family, and Jo [Joseph Sinel] is my great uncle who I knew well. Oh what a colourful character he was and he would have a laugh at what has been written. So true all of it. I remember his caravan well when he visited us in NZ. Our family relocated to Australia in 1970 but never lost touch. Thank you for your article and I now know where my children get their visual art skills from, one of which excels in the area of design. Glad to see talent has resurfaced. He would be proud. Thanks again for a most enjoyable read. Sally, Sales Assistant Melbourne

Thank you very much for your fine piece on Joseph Sinel. I never had the pleasure of meeting him but he knew both my grandfather and my father. My father (Robert Matthiesen) was a well known art director and designer in the Seattle area and Jo Sinel was considered iconic and much admired in our family as I grew up in the 1950's. Your piece filled in some gaps of information and provided excellent source material. Thomas, Duvall, Washington, USA

I was born in Tauranga but came over to Australia with my father's work. My great uncle is Joseph Sinel whom I loved dearly. Very, very eccentric fellow but a gem all the same. My son and I march with the Kiwis every Anzac day in Melbourne. He proudly wears my Uncles' and Grandfathers' medals. All our family is from New Zealand - Bay of Plenty, Auckland and the Bay of Islands. Love reading about NZ, very passionate about my roots. I recently got a tattoo of a Koru on my foot when my Dad passed away and get great pleasure in explaining its meaning when asked. Looking forward to a trip back home soon.

I am researching my family, and Jo [Joseph Sinel] is my great uncle who I knew well. Oh what a colourful character he was and he would have a laugh at what has been written. So true all of it. I remember his caravan well when he visited us in NZ. Our family relocated to Australia in 1970 but never lost touch. Thank you for your article and I now know where my children get their visual art skills from,one of which excels in the area of design. Glad to see talent has resurfaced. He would be proud. Thanks again for a most enjoyable read. Sally, Sales Assistant Melbourne