Hello. Its been a while. My heart is full. I’m in the mood to write.

In recent times Taape and I have been trying as much as is possible to live out at Ocean Beach, in the old lady Hariata (Mohi) Baker’s house at Waipuka. The other night the perigee moon cast its shoon across the bay. Its phosphorescent footprint was intense. The flouresence generated such high lux that the beach itself looked like a stark Vincent Ward movie set. The moon, being at its closest point to the earth in 20 years exerted a stronger than usual lunar pull and created a king tide that pushed white froth and spray as far up the shoreline as I have ever witnessed.

Perigee Moon Ocean Beach August 2014

The sea roars as I write this; not an angry roar but a perpetual aural reminder of Tangaroa’s busy domain. It creates a soothing ambience. There’s no one around. The beach cottages at Waipuka are mainly deserted. We are pretty much on our own. There’s no internet or cellphone coverage.

Its here that we have purposefully come to take a break, to stop for a while in recognition that we need space and silence enough to allow grief to be acknowledged and hear it speak to us without being drowned out by the intense and busy nature of our lives.

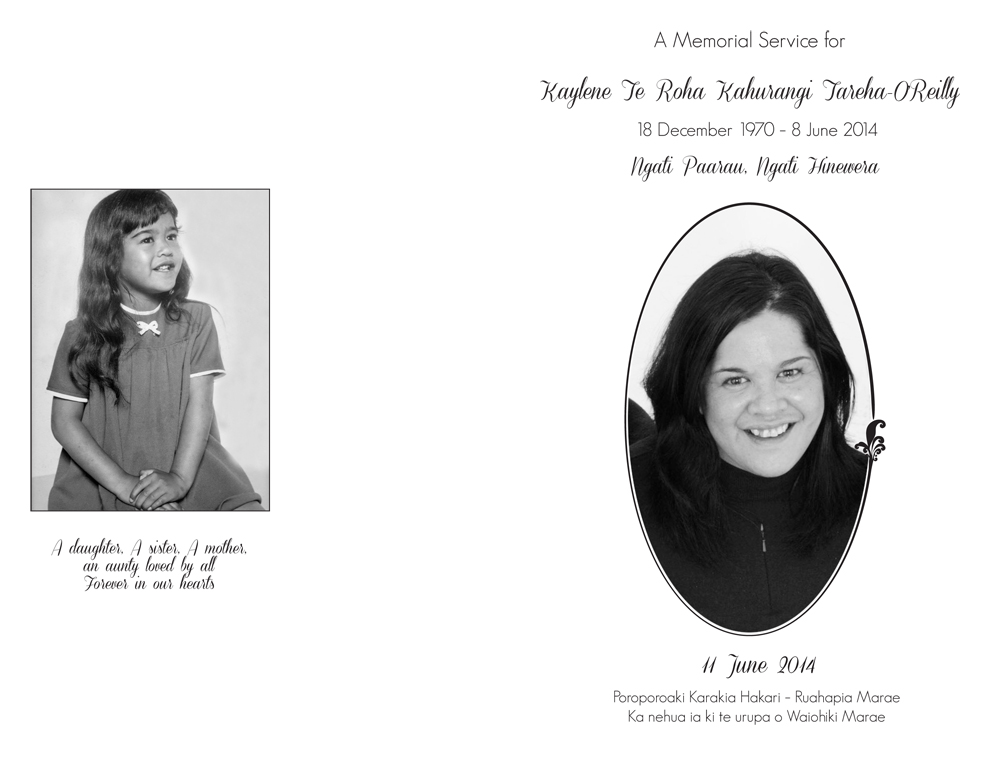

The grief of which I speak relates to the recent death of our oldest daughter Kaylene. She had an eventful life. I wrote about a near miraculous occurrence concerning her in my Nga Kupu Aroha blog series “Nga mea o te ora” (24 March 2006). In brief she had fallen ill with a merciless virus which had caused brain stem encephalitis – a swelling at the most vital spot near the base of the brain. The doctors had called us all in to the intensive care unit to advise us there was no hope for her, and recommending that life support should be withdrawn. I called for the Catholic priest who began to administer last rites. Taape was having none of it and insisted on the services of a tohunga, her cousin Tahu [Rangitihi (John) Tahuparae]. Tahu duly arrived and began his chant. The priest looked at me quizzically and I said “It’ll be alright father. You look after AD, he’ll look after BC”. After Tahu’s karakia Kaylene sighed, and Tahu proclaimed that she would be alright. And, so she pretty much was, for the next seven years, holding down a fulltime job and bringing the two youngest of her four sons, Te Roera and Tumanako Jujnovich, through a crucial part of their childhood.

When she fell ill this time there was no reprieve and during the late hours of 8 June 2014 she joined the legions of her ancestors. Because Kaylene had spent all of her working life in Wellington we decided to hold a service with her there so her friends and workmates could say goodbye without making the trek up to Hawke’s Bay. We were offered use of a little church-based marae at Moera in Lower Hutt. It is called Te Kakano o Te Aroha – the seed of love. The marae’s foundation arose out of an entente between the Tuhoe prophet Rua Kenana and the Presbyterian missionary John Laughton.

Some of the marae folk were related to Taape through her Tuhoe line and I had worked with others in Te Whanganui a Tara Maori Rugby League. The place was packed for Kaylene’s Wellington goodbye, the rites being a mix of Presbyterian and Ringatu.

The weather was foul as the cortege wound its way home. A rain bomb had dumped its load along the entire east coast. We’d been all keen to bring Kaylene straight to Waiohiki but, since our whare has been burned down and we have no place of shelter, these cold wet conditions rendered marquees inhospitable and insufficient to manaaki the mourners. A request was made by Ngati Hawea from Ruahapia Marae for her to rest there. We gratefully agreed. Some of the family were unhappy with this decision saying that this was not our marae. That lack of understanding was soon addressed in the first welcoming speech at Ruahapia during which the kaumatua recited 52 generations of the whakapapa that connected Kaylene to the marae. Indeed on the wall above her coffin were photos of her great grandmother and great grandfather and her great great grandmother.

As Taape kept on pointing out to our mokos, “all the marae around here are our marae – we belong to them all, not just one.”

Over a night and a day we spoke and laughed and prayed. Ngahiwi Tomoana, the Ngati Kahungunu tribal chief came and had us in fits with his tales of his exploits with the Tareha whanau. There were many poignant moments too as the whanau gathered – tears flowed freely.

Father Don Hamilton, our family priest, led the final service. Don taught me English when I was a 16 year old at St Pats in Timaru. He must be in his mid-eighties but looks the same as he did in 1968. Fr Don was the marriage celebrant for Taape and me thirty eight years ago and he has officiated at the majority of our immediate whanau events, christenings and 21sts and the like.

Kaylene as our flowergirl Waiohiki Marae 15 May 1976

So, Fr. Don led us in prayer for the confident passage of our girl’s spirit into the hereafter. Immediately after the main service concluded we shared in kai, the hakari, a lavish feast.

Normally, in Kahungunu, the hakari would occur only after the internment, but in this instance, and in light of the continuing deluge, we were allowed to adjust the tikanga. Accordingly, after kai, we took our girl to her final resting place in the arms of papatuanuku at the Waiohiki marae urupa.

Our Ngati Paarau whanau and friends had gathered. Under a bleak sky Kath Hawaikirangi led nga anahera, the angels of the Ratana Choir, in multiple harmonies as her brother Hoani delivered the rites of Nga Morehu.

Kaylene was placed at the foot of her aunty Huia and joined the company of her tupuna. Ringatu/Presbyterian in Wellington; Catholic at Ruahapia; Ratana at Waiohiki; it was a trifecta of liturgies.

Takoto mai e toku putipiuti. Moe mai, rest in peace.

Our mokos Te Roera and Tumanako Jujnovich, Kaylene’s youngest sons, at her graveside, Waiohiki.

Apiti hono, taito hono, te hunga mate ki te hunga mate, apiti hono taito hono te hunga ora ki te hunga ora. We will leave the dead with the dead, and we will turn our attention back to the living.

Grief is a process. You can busy yourself and try to outrun it but that’s illusory. Immediately after the tangi once all the rellies had departed I threw myself back into work but found myself a bit discombobulated. I turned up at Parliament for a meeting with Minister Turia a month early and missed other planned events entirely. The other day I was starting a meeting with a karakia. It was being held with ACC to discuss the lack of progress being made with a housing solution for a young girl with tetraplegia. I am her advocate. She may be severely disabled but she has spark and verve and warmth. And she lives. As I farewelled the dead I thought of Kaylene and for a moment I was overcome.

Work has begun to feel like Groundhog Day. Same old. I seem to be busier than ever. Then it occurs to me that maybe I’m just taking longer to do things. Change is required. Accordingly, currently, life’s a beach.

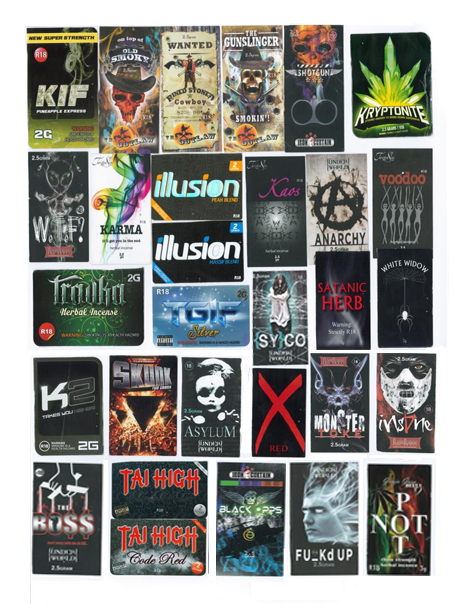

Over the last year my team and I have put a huge effort into the development of the policy around new psychoactive substances. These have flooded into New Zealand since the turn of the millennium. They mimicked the effects of illicit substances but in themselves were not illegal. When these products caused harm and were banned chemists would simply change some of the compounds and launch a new product.

The difficulty for medical and health sector staff was that they simply did not know what the active ingredients in these substances were, so it became problematic to know how to respond and treat users who were experiencing problems (assessed at <10% users).

The NZ Government proposed to counter this new issue by creating a regulatory framework that put the onus of proof that the product was not harmful or was of low harm onto the manufacturer. The range of products was breath-taking, and if the product graphics are anything to go by, was aimed at young people. Dollars flowed. Lots of them. There were about 3,000 points of sale (including corner dairies) and hundreds of products. Driven by notions of relative value and the fact that they were legal Kiwi recreational drug bingers embraced them till they hurt.

The Sale of Psychoactive Substances Act (2103) went through Parliament at 119 votes to 1 – and that sole vote against was cast by John Banks in favour of the beagles – he didn’t want testing on animals. It looked like we had grown up politically in terms of health oriented drug policy.

However as the “legal highs” regulatory framework kicked in, and users were funnelled into a few points of sale, the burghers of provincial New Zealand in particular were confronted with the reality and scale of New Zealand’s recreational drug culture. It was in their face and they didn’t like it. A nationwide moral panic erupted, led in the main by provincial mayors.

It has been said that life imitates art. Have you ever seen the HBO TV series “The Wire”? Its storyline focuses on drugs and politics in Baltimore USA. In series three a pragmatic cop, Major Howard “Bunny” Colvin, decides to decrease crime in his district by establishing a free zone in an abandoned ghetto. Drug dealers are invited to ply their trade with impunity as long as they stay away from their traditional downtown “corners” and avoid violence. The dealers take up the offer – they nickname the area “Hamsterdam.” Reported crime drops and health workers are able to concentrate their efforts on reducing drug related harm by easily accessing the user community at one central location. When the Mayor finds out about what is being done his first instinct is to shut it down. But then he is confronted with the reality of a 14% drop in felonies and much evidence of widespread community support within the areas no longer afflicted with the drug trade. The Mayor is tempted to let the arrangement continue. One of his top advisors tells him “this is legalising drugs!” The Mayor muses that he’d like to keep this thing going “without calling it what it is!” Of course the brave experiment is disestablished. The “game” shifts back to the corners, and the suite of harmful impacts associated with drug use – including imprisonment – is revived.

It has parallels with what has just happened here in real day Aotearoa.

I’d seen the resistance to the policy building up amongst the three east coast mayors, Meng Foon in Gisborne, Bill Dalton in Napier and Lawrence Yule in Hastings. Lawrence’s opinion was important because he chairs Local Govt NZ.

Last year I thought Lawrence had just been badly briefed when he came out in the local papers accusing Central Government of being “weak kneed” by introducing this policy. My response was that in fact Government had been “clear headed.” There was a public protest about the new policy held at the Hastings Clocktower. At the protest I distributed a little flyer explaining the policy and criticising the Council for the approach it seemed to be taking. One of the Councillors organising the protest became very agitated by my activities – in fact virtually apoplectic – and wanted to have me removed from the concourse. Eventually I was accorded speaking rights and was allowed to present a counter argument. I was a lone and dissenting voice but was heard in a respectful silence. I didn’t realise at that point that the Councillor owned a shop that was adjacent to an approved point of sale.. The high foot traffic of ‘undesirables’ buying their fix were seen to be a disincentive to people coming to her own shop. It wasn’t just a moral issue.

I then noted Mayor Meng Foon stating in Neil Reid’s columns in the Sunday News that he wanted to declare Gisborne a Psychoactive Substance Free City. It would have stuffed up the liquor trade. I thought Meng’s stance was paradoxical. He is the mayor of an area where use of illicit recreational substances is endemic, particularly in terms of comparatively high rates of methamphetamine consumption and what, again relatively, might be considered to be a regional culture of intergenerational use of cannabis. I would have thought that he would support a policy that was attempting to get a grip on this complex issue. I ran into Meng up at Te Horo Marae, situated at the mouth of the Waiapu River, when we were at Dudu Fox’s tangi (Derek’s dad). I hit him up about his stance. He said, “Denis I know the rationale for the policy but I’m an elected official and this is what my community want me to do.” Well at least he’s frank.

In the meantime the Ministry of Health was too slow in implementing the regulatory framework. They just didn’t have the resource to deploy and consequently couldn’t respond quickly enough or comprehensively enough to counter misinformation and hype about the sale of psychoactive substances policy.

Furthermore the protective mechanics of the policy were not sufficiently promoted.

For instance there was a process in place for citizens to report harmful effects – even subjective assessments – of specific new psychoactive substances. A certain number of reports would merit the product being removed from sale.

Indeed the number of products on sale reduced by about 75% and this seemed to contribute to a profound reduction in the rate of those seeking medical treatment as a result of ingesting these substances. Secondly the numbers of approved points of sale were dramatically reduced: by 95% from around 3,000 to 170 nationally. And herein lay the rub. In the Hawke’s Bay for instance the twin cities of Napier and Hastings ended up with having one approved outlet between them. There was constant traffic and even queues before opening time. It was a highly public insight into Kiwi drug culture. [Just imagine though if there was only one approved outlet for the sale of alcohol across the two cities – OMG]. The provincial mayors – the mayors of the major metropolitans were noticeably silent – kicked up a storm. In Hawke’s Bay mayors and councillors began addressing public rallies protesting against what were being called “legal highs.” The most prominent product cited in the protests was one called K2. In fact invariably there were banners or protest signs calling for K2 to be banned.

This photograph was taken at a demonstration in Hastings on 5 April 2014. The substance the protestors wanted banned, “K2”, had actually been prohibited from sale since May 2013.

It was against this background that a moral panic began to build. I thought I’d try to promote some informed debate so I worked with Kevin Tamati to organise a public forum about the issue. I invited all three mayors and sent them copies of background information. Included in the package was the “Wellington Declaration” that emerged from a summit held in August 2013. I reckon it’s the most current and comprehensive summary of the New Zealand issues around the use of recreational substances (www.drugfoundation.org.nz/wellington–declaration/declaration).

We decided to livestream the event and using Google Hangout organised for Peter Dunne, the Minister responsible for the new legislation to be available on line as well. See an edited video here

The gig was well attended (about 300) and had an online audience of about 150. But the mayoral stances were fixed. Instead of trying to make the policy work both baby and bathwater were being tossed out. Populist politics were trumping evidence-based policy. At a national level the political cost became unbearable.

The Government was compelled to intervene by effectively placing a moratorium on the policy. Legislation was introduced under emergency and at 12.01am on May 8th 2014 the right to sale of psychoactive substances (other than alcohol and nicotine) was rescinded.

I just threw my hands up and thought “Why bother? Why put all that effort into informed debate and development of policy aimed to reduce drug-related harm?”.

Ah well, it’s a times like these that I remember the sage Muldoon coaching me on providing advice to Ministers: “Tell ’em straight up Denis, give your best advice, be courageous, but if they want to do something else then just remember, no one voted for you.” We’ll take up the drug policy debate again sometime after the election I suppose. The issue won’t go away.

Another poll driven issue (I presume) is the electioneering around gangs. Earlier in the year Police Minister Ann Tolley went to America to look at ways to deal with gangs. She came back with what I thought at the time was an enlightened perspective, saying that we can’t arrest our way out of the gang issue and that the solution lay within the community. Bravo!

In May TV3’s 3rd Degree ran a programme on some efforts that a number of us have been working on for years, namely co-existence between Mongrel Mob and Black Power whanau.

It’s a constant theme of the Nga Kupu Aroha series. This TV programme went astral, and has had something like 92,000 downloads and that’s growing. It is the most watched programme for 3rd Degree this year. That demonstrates the high level of community interest in the whole gang topic.

A week or so after the programme I sat down with Mike Bush the Commissioner of Police to talk about Government’s then impending fresh gang policy. The word around the traps was that it was a new approach and was based on carrot and stick.

I gave him my view that essentially gangs are irrelevant: don’t have a gang policy, have a community policy; focus on behaviour not affiliation; call organised crime what it is, organised crime, regardless of who is up to it; recognise that NZ can’t police its way out of the social canyon of trapped lifestyles -this will take leadership from within communities and it may well be that some of those leaders are currently in gangs. It was an affable exchange.

Mike Bush impresses me. His apology to Tuhoe, about the way in which the Operation 8 Raid was conducted, showed awareness and sincerity. Appropriately he first personally approached each whanau in turn and then later, the community as a collective. He intelligently differentiated between the rationales for the raid itself and the way in which it was conducted.

I hope he can apply the same approach to the gang issue. Its that ability and preparedness to differentiate between organised crime and people in trapped lifestyles that will lead us to our own solutions in Aotearoa.

It all came home to me after watching The Dark Horse.

I think it’s the most powerful Kiwi movie I have seen. It works on multiple levels. Some of the dialogue is insight of Shakespearean quality. There are poignant soliloquies. One of the threads to the story is that of misdirected love within a trapped lifestyle. The gang dad, Ariki, who we finally learn is dying, believes the most loving thing he can do for his son is to see him patched up. In the end, without schmaltz, whanau wins out. Wayne Hapi (who plays Ariki) was himself a member of the Black Power for over a decade. His portrayal was visceral, based on personal experience.

It occurred to me that we should show the movie in every prison and afterwards ask inmates. “What do you want for your children?” Theatre often provides us with a pathway to discuss the otherwise out of bounds topics.

I’d been up in Auckland at an AUT think tank type affair connected with my PhD studies. I spent half a day surrounded by professors and doctors. The combined brainpower could have generated light. I was the most under-qualified person in the room.

We were discussing new approaches to research especially around issues of disability and health – there’s a concept called liminality that interests me. As the korero flowed and tapped into different disciplines and research methodologies it seemed to me that we were approaching the “emergent epistemology” of transdisciplinarity with which I’ve been struggling since my Masters. Heady stuff but Its cool fun nevertheless, like surfing thought.

On the way home, hardly at the Bombay hills, the phone started going mad. There was going to be a post-cabinet press conference and a new gang policy was to be announced in the afternoon. (It’s an election time tradition). Would I do TV1 Breakfast? Turn around, go back to Auckland. I get to read the press release from the Minister of Police and listen to the PM on National Radio. Organised Crime, Outlaw Motorcycle Groups and “gangs” are all conflated into the same bundle. And then the media maelstrom hit: National Radio, the multi-programmes of Radio Live, Newstalk, Waatea, Maori TV. I endlessly repeat the same mantra as I gave to Mike Bush. Separate out issues of organised crime from the behaviours of those in trapped lifestyles: international networks bringing in meth aren’t in the same domain as families in trapped lifestyles experiencing domestic violence. After the election we really need to have this discussion in a multi-partisan way, just like the drug policy debate. These sores have been incorrectly diagnosed and inappropriately treated for too long.

Heading home again I called in to the Headhunters (East) clubrooms to pay my respects to the Morris whanau over the loss of their son Connor Morris. The club’s base is an impressive set up. It bespeaks discipline and organisation. The family and club were treating the premises in a way similar to a marae, and they had Connor laid out in a large lounge upstairs, surrounded by his loved ones and respectful club mates. I gave my poroporoaki, saying to Chris, Connor’s dad, that I knew the deep and private pain of losing a child.

Late last week my team at AWA Transmedia Studios (AWA stands for Aroha [Love] Whanau [Family] and Awhinatanga [Community support] were awarded an E Tu Whanau Kahukura Award for leadership in the pro-social use of mobile media (www.awatransmedia.com). We use digital storytelling to uplift and support people and projects. There are little campaigns to subtly promote positive behaviours and reconnect individuals and whanau with their ancient traditions and inner strengths. One of the story themes is built around the kuaka (bar tailed godwit). It uses these long haul champions as a metaphor for whanau strengths. There are some heart-warming insights. Go have a look on www.hekuaka.co.nz.

Another AWA project is to counter cyber-bullying (Te Punanga Haumaru). It does this in two ways, firstly by promoting uplifting talk (korero awhi) and secondly by developing a cyber-tikanga – expected behaviours based on the E Tu Whanau values of:

- Aroha – expression of love/ feeling loved;

- Whānaungatanga – it’s about being connected to whānau

- Whakapapa – knowing who you are;

- Mana/manaaki – upholding people’s dignity / giving of yourself to others;

- Korero awhi – open communication, being supportive; and

- Tikanga – doing things the right way, according to our values.

To the best of my knowledge this “cyber tikanga” is the first indigenous effort to take a strengths based approach to manage the interpersonal risks associated with social media.

The Kahukura (Leadership) Award was presented at an event at Te Hirangi Marae in Turangi by Ngati Tuwharetoa paramount chief Tumu Te Heuheu. E Tu Whanau is a Maori programme designed to eliminate domestic violence. It arose out of the Taskforce on Domestic Violence but took a strengths based Maori approach to the issue (let’s do this) rather than the pathological (stop doing this) focus taken by most domestic violence programmes. There was a who’s who of family action activists at the event including that Maori Boadicea, Merepeka Raukawa Tait, and it seemed to me that a deeply rooted Maori movement designed to effectively counter domestic violence is beginning to form.

Gypsy Pitman picks up the challenge at Wellington’s 40th. Artie is in the brown jersey standing behind Gypsy.

It was with these thoughts in mind that I went down to Artie Beazley’s tangi at Rehua Marae in Christchurch. Artie was a Black Power president. Like many others he’d drifted to the south in the late 1970’s and became part of the Maori sub-culture of Otautahi. Artie was, even amongst gang members, a “character”. There was a huge turnout including BP rangatira from all around Aotearoa, Mark and Gypsy Pitman from Auckland, the founding president Reitu Harris, Ngapari from Taranaki, the Mc Kinnons, Eugene Ryder, even members from Australia representing Artie’s whanau connections there.

Rehua Marae has its roots in the Maori Trade Training programmes of the 1960’s. By definition it is a taurahere marae, designed as a point of connection for those Maori from outside the Ngai Tahu tribal area. Today the meeting house (Te Whatu Manawa Māoritanga o Rehua) is a central point for a wide range of activities. And so it was here that Artie was brought. I went down with Nath who was representing Hawke’s Bay. During the mihi-mihi I thought I noted that one of the kaumatua on the paepae was wearing a patch, and, so he was. On the final day, during the service, Reitu asked me to speak on behalf of the brothers. This E Tu Whanau stuff had been running through my brain, and as I rose to speak I had one of those moments where the fusion of various thoughts and ideas crystallised. I had clarity. It was the constellation of Kairos. Here we were in a whare that arose out of a scheme of proactive engagement of young Maori men into employment by way of trade training. It was tremendously successful but was disestablished because of the “market will provide” ideology. In its place we saw work gangs morph into street gangs. The Crown now vilifies these clusters of gang members and is attempting to further alienate them from their communities by banning patches and alleging that they constitute organised criminal groups. But here at Rehua the patch and the affiliation were irrelevant. The people were simply who they were. As I looked around the crowded whare I saw Artie’s children and grandchildren – his whanau, and it seemed to me that they had come home. The whare and the tikanga it represented held the solution for their future wellbeing. Our membership, Artie’s membership, of Black Power is irrelevant. The answer lies in a different direction – te mana kaha o te whanau.

If I thought death had done with me for a while, I was wrong. Yesterday I spoke at the service for Helen Wilmot Mason, MNZM, who was in her 100th year.

My personal connections with Helen go back to the 1980’s with Barry Brickell and through Para Matchitt, Jake Scott, and Bay Riddell at Otatara, and through her time with Ngoi Pewhairangi at Tokomaru Bay. She supported us through the work cooperative movement and various political causes of the day.

The last stanza of our relationship arose out of an encounter in 2005 at the Pukeora Estate Arts Festival where she told us that she wanted to come and live with us at Waiohiki. It took a little while but on the 16 April 2006 the then Deputy Prime Minister Michael Cullen officially opened Helen Mason House, and thus, her spirit resides within that whare, and it will serve as a reminder of her and be a wellspring of quiet creative disobedience long after all of us have passed from the mortal coil.

Helen saw two world wars and the seismic shift in New Zealand’s cultural landscape. She was a kuia, a kuia Pakeha and the matriarch of the Waiohiki Creative Arts Village. She is also considered by many to be the mother of pottery in Aotearoa.

Kuia are appointed by their people because they are seen to have the capacity to teach and guide both current and future generations. These notions transcend race and culture. It’s not a formal thing, or a process like an election (thank God!), but the reality of the role is signified by the fact that people came to Helen for wisdom. This dear lady gave us that in pots.

Helen worked with Papatuanuku in many ways and forms, potting with clay, weaving with flax, and weaving with wool. She returns to the arms of mother earth in the form of fine ash. As I noted (o-wryly) in my poroporoaki before she departed for the crematorium, this was her final firing.

I’m said and done. Arohanui. Denis