Glaxo SmithKline, the largest pharmaceutical group in the world, had its origins in a place far removed from the centres of world commerce: a dairy creamery in Bunnythorpe, near Palmerston North, and a general trading company started in Wellington, New Zealand in 1873.

To many, the town may seem an ode to nothing in particular but, as is often the New Zealand way, the ordinary masks the extraordinary. For amid the tattered buildings lies a mark of early history. High on the broken-windowed, former dairy factory – with its peeling paint, rusted roof, creeping moss, and broken-down, nailed-up doorways – is a plastered edifice carrying the name, Glaxo, and it is here the famous brand was born.

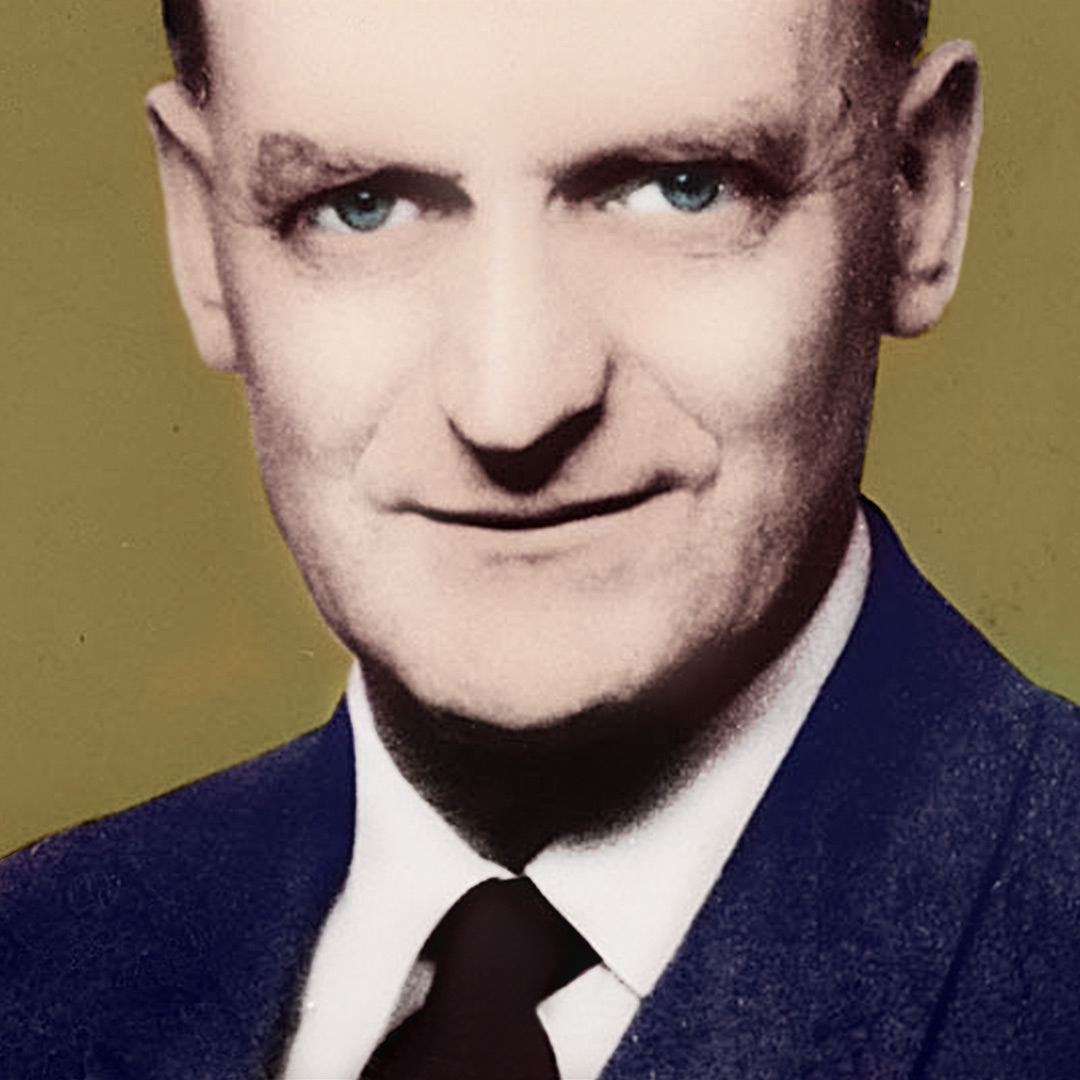

It is a mark of innovation that grew from nineteenth century, pioneering New Zealand under the auspices of the profoundly Jewish, Joseph Edward Nathan, a mercantiler and entrepreneur, reputed to have been a man of “extraordinary foresight”. He was to found a brand name that would win wide acclaim, nurture the national ego and become central to the impulse of a colony in its formative years.

Now, beyond the edge of the true millennial change, Nathan’s commercial legacy, Glaxo, has extended his original vision. On December 27, 2000, the name born in a frontier New Zealand town was, in an age of globalisation and corporate dominance, hoist by merger to the masthead of one of the largest pharmaceutical behemoths the world has known: the UK-based chemical kingdom of GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

By today’s standards, it is enormous. Based on 2001 figures, their revenue stands at $US27.4 billion; and is second in the world to Merck in terms of profit (GSK = US$6.38 billion at last report). GSK holds a seven per cent share of the global pharmaceutical market; it has the largest R&D budget at $US3.7 billion. Put another way, doctors world-wide write some 1,100 scripts for GlaxoSmithKline products every minute.

Such is the legacy, and Nathan rightly takes his place as a man who has stood at, and peered out from, the New Zealand Edge. He became an iconic figure who showed the way for genuine entrepreneurship and helped steer New Zealand’s development.

From the East-End of London to the Colonies

Nathan was born into inauspicious circumstances on or about March 2, 1835, to a family of Orthodox Jews in outer London – poor tailors living near the East-End. His father, Edward, was said to be “a charming old man with very little (sic) brains”, his mother, Rachel, “a highly intelligent woman …with very little education”. The area was impoverished and the people in bondage to the class-strictures of the times.

From birth, Nathan suffered from asthma and keenly felt the tyranny of the damp and polluted London air. Even so, he would show commercial acumen and entrepreneurial zeal by age 12. He persuaded his father to don a tailcoat and silk hat and travel by horse and gig to boost sales. He also saw export potential but his father was disinterested, so the boy languished with a poor education and limited expectations.

Poor health and poverty may have fuelled Nathan’s desire to escape the stale rigidity of industrial England, where opportunity was reserved for the privileged few and class discrimination was a life sentence. His early days led also to a belief in a greater, collectivist social good, egalitarianism and “selfless and dignified citizenship” – themes to become admired in colonial New Zealand and part of the national character.

Nathan’s opportunity arose when gold fever struck Ballarat, Victoria, in 1851. His mother died in 1852 and Nathan left for Melbourne on the William Akers in 1853, amid others dreaming of fortune and a new order. But he was soon apprised of his immediate ambition. An Australian policeman, observing his lack of physique and general well-being, advised him to instead set up shop to the fortune seekers.

Melbourne circa 1853 Source: Glaxo UK

Across the Tasman and into Business

Nathan started a miners’ store in Melbourne but lacked sufficient capital for growth. Frustrated and with family connections in Wellington, he wasted little time leaving for New Zealand. He arrived in the port of Lyttelton, December 20, 1856, aged 21, and set north for the then small commercial centre of Wellington.

If he thought Victoria harsh, New Zealand was a step beyond. Immigrant ships had begun arriving just ten years earlier, the country lacked transport and suffered extreme isolation. Wellington itself was a rugged town of just 3,200 people, 13 hotels, two theatres, two newspapers and three fire-engines. The country depended upon a few merchant ships each year, which took three to five months to arrive.

Although the Treaty of Waitangi had been signed in 1840, the New Zealand Wars of the 1860’s awaited. Skirmishes would yet force the abandonment of business and towns. As one historian of the time said: Maori “watch as pakeha usurp the lands and insult their laws and leaders … [They prepare for a] brave and bloody last attempt to save their old ways of life.” These were not easy times; even many merchant ships would stay away.

On January 1, 1861, after marrying Dinah Marks, “according to the rites and ceremonies of the Jewish faith”, he partnered his sister’s husband, Jacob Joseph, in business. That would dissolve in 1873 and within days of dissolution Joseph Nathan and Co. was established: a mercantiling company that would spawn Glaxo and enter the pharmaceutical world on a pathway to world leadership.

But for now even the name Glaxo belonged to an unknown future and Nathan dealt in simple stock including colonial produce, fancy goods, clocks, jewellery, ironmongery and patent medicines, fore-runners to latter-day vitamins and drugs. Perhaps as a foretaste of things to come, he sold the general tonics and cure-alls of the day, such potions with exotic European names as Wolfe’s Romantic Schiedan Schnapps.

The Joseph Nathan & Co building is on the far right of the photograph, Corner Featherston and Grey Streets, Wellington, Circa 1874 Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

A Matter of Religion

Orthodox Judaism permeated Nathan’s world. It was inseparable from the man and his life, shaping his personal, community and business values. Strict and pious, he was to host weekly synagogue at home until one could be built, would become the first president and a leader until 1895. Finding an employee working at his office on the Sabbath, he was said to have sharply evicted him, warning of future dismissal.

Ethical and honest dealings were at the Nathan core. He developed a strong social conscience, caring for the less privileged in society and contributed to charities in time and money. Such values were attributed in the New Zealand Mail, in 1907:

“Mr Nathan joined to his integrity a cool brain, untiring energy, and a wide and profound knowledge of business. He was a man of great resource and judgement … [having a] “firm belief in the virtues of straight shooting, a cheerful confidence in the years ahead and an invincible determination to attain by honest means, honest ends.”

A letter he wrote to his sons after writing his final will in 1903 – demonstrating either failing eyesight or a lack of interest in grammar – also gives insight to his views.

“My Dear Sons … I have tried my best to be equitable towards all my dear children … I feel the great God of Israel has been pleased to bless me abundantly … we are only trustees [and] all is not given us for our own use …used only for selfish pleasure. All my life I have held these views … sharing with others, seeking where help was wanted and acting according to the judgement vouch-saved me, do likewise you will find happiness … I hope each and all of you will … feel as I have felt it is a blessing to [be born] a Jew. Be proud of your Birthright and all men will respect you …you as well as I …will be called upon to make sacrifices for your religion, do it with pleasure, … esteem it a privilege and God will bless you as he blessed your fathers … I need not tell my sons that Honour Truth and Integrity are sure roads to success …”

A Crystal Vision

But if the values were to be based on deep Jewish principles, without doubt Nathan’s commercial growth depended upon his actions. He sought to expand. Technology, shipping, transport, land acquisition and finance were to become key interests. In this expansion much of his reputation for colonial and business vision was built.

His first technological revelation was refrigerated shipping and in 1882, the Dunedin made its first journey, delivering near perfect product to the UK. Two years later, seeing advantage, Nathan helped pioneer frozen meat exporting, so vital to the colony’s fortunes, and became chairman of the Wellington Meat Export Company.

The Dunedin being loaded with the first meat to leave New Zealnd under refrigeration. The ship left Port Chalmers on 15 February and arrived in England on 14 May 1882. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

He then moved to secure leadership in shipping. He helped begin a company that chartered sailing ships for freight delivery, proposed a Wellington Harbour Board and became its director, and set up a shipping repair company, the Wellington Patent Slip Company. He also headed the influential Chamber of Commerce.

Next was the Nathan bid to free himself from financial constraint, at least in the short term. He visited London in the mid-1880’s and secured financial backing from the big London banks, sums that were then unavailable in New Zealand. He opened a London office and an entr?e to the all-important London-based markets of the UK.

But the effort was not without struggle. In 1880, a Royal Commission opposed the Manawatu railway. The government shelved the development, citing expense in a decade of depression. But too much was at stake. Nathan helped to finance the then private project and in November 1886, the first train rattled into Palmerston North. The elements for the dynamic expansion of Joseph Nathan and Co. were in place.

In a speech at the opening of the Manawatu Railway in 1886, Nathan spoke of the benefits of “well directed energy and perseverance” – saying this would always lead to success – and of “united action for the common good”. Left unsaid was that these works for “public good” were also very much for the good of Nathan and his interests.

Nathan’s reputation had now solidified and he was pressed to enter politics. He cited poor health and was perhaps mindful of anti-Semitic attitudes in colonial society. Nathan had limited respect for the day-to-day machinations of politics and did not believe politics was, for him, a forum for the effective advancement of New Zealand.

Opening of the Wellington – Manawatu railway, November 1886 Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

To Bunnythorpe and Glaxo – the Birth of a Brand

Nathan was now on the move. He built or bought into about 17 creameries in the Manawatu and held shares in dairy factories. He formed associations with dairy cooperatives and later expanded into the Waikato. With capital again in demand, the need for a limited company was debated, strenuously, with his sons. Joseph Nathan and Company London Ltd was registered in 1899, with Nathan as chairman.

The company then became interested in dried milk. By 1904, it was to secure a drying process that proved flawed, but refined it. This was a masterstroke, for although dried milk was far from exclusively Nathan’s idea, it was soon seen as a counter to growing concern at fresh milk: bacterial disease, particularly “the liquid scourge”, Tuberculosis.

It was to Bunnythorpe that Nathan turned to build his first dried milk factory under the brand name Defiance, but this step was not without a hitch. A milk factory competitor is believed to have set the first factory alight and blow up the second by gelignite. Suppliers and consumers too would initially resist the product – Defiance was not an appealing name for infant food. To ease the way and propel market impact, a new name was proposed. The Nathan directors settled on Lacto but (thankfully) this could not be registered because several similar names were already in the market. By adding and changing letters, the name Glaxo evolved and was registered on October 27, 1906.

The first dried milk factory in Bunnythorpe. Unknown source

Infant Health, Ad Campaigns and a World Famous Food

Although consumers were initially suspicious of dried milk, the risks of so-called fresh milk were increasingly subjected to medical studies. In 1907, a trial in Sheffield found infants on dried milk suffered 7.9 per cent mortality compared to 14.5 per cent regionally. In 1911, a London drought led to a gastroenteritis epidemic, killing 3,000 babies, but babies fed on dried milk were less vulnerable. Health authorities promoted dried milk and Glaxo won the support of New Zealand infant specialist, Dr Truby King. The emergence of the Great War in 1914 was then to provide substantial demand.

But any advance was precariously won. Indeed, Glaxo competed with 300 other brands of dried milk in the UK. To build market share, a front-page London Daily Mail ad was tried in 1908. Its slogan – ” the food that builds bonny babies” – later became famous, but the ad generated just 57 responses. Consumers appeared to have shunned Glaxo and the company fingers were considered burnt. The future of Glaxo was now questioned.

Glaxo postcard. Glaxo UK

In hindsight, the one-off ad-campaign was unlikely to create market penetration and the 57 responses were perhaps a good response given the lack of supporting communications. Indeed, there was no back up campaign, no support material, no repeat ads and such a dense market was unlikely to react, even though the ad was placed on the front page of a popular daily.

If Glaxo was to continue, competition and consumer resistance were the major obstacles that had to be overcome. In the face of such stern competition, and total sales in the seven months of trading in 1908 reaching just 1900-pounds with a loss of almost 3,000 pounds, it is not surprising some managers became gun shy. One of Nathan’s sons, Alec, stepped into the breach, carrying the argument step-by-step to continue Glaxo.

His persistence would ultimately pay off but from 1908 to 1910 Glaxo failed to make a profit. In 1911 it pocketed just 500 pounds on a turnover of 10,000 pounds and during this time Glaxo could easily have disappeared. But the product was kept going, and by 1918, it dominated the sales of Nathan and Co Ltd with a turnover of 550,000 pounds. There would be no looking back. Ironically, it was Alec’s strategic approach to promotion that had effectively held the key.

In time, his strategies would be considered ground-breaking. The Glaxo Baby Book was created in 1908 after nurses employed by Nathan found it difficult to answer the flood of mothers’ inquiries. By 1922, a million copies of the baby welfare books were published, Glaxo was a household name and the book would endure for 60-years. Individual contact became important. Person-specific mail was sent to doctors, personal visits made and birth notices used to mail mothers. “Direct marketing” was unheard of then.

Source: Glaxo Archives

The Advertising World magazine was to say this work was the “most successful form of advertising of the present day”. In 1913, they said: “seven years ago Glaxo was known among a very small section of the community – today it is not an exaggeration to say every mother at least knows about Glaxo”. Perhaps conclusive evidence of Glaxo’s acceptance was its appearance in Virginia Woolf’s 1925 novel, Mrs Dalloway.

An End and a New Beginning

Joseph Nathan died in London on May 2, 1912, after a period of ill-health. He was 77 and his place in history was secure. His death was to be both an end and a new beginning. In 1912, Glaxo and the company was on the verge of major success. The future was now to be dominated by the leadership of Nathan’s sons.

Nathan’s life had by now completed a circular journey. From 1890, Nathan had no longer lived permanently in New Zealand, although a frequent visitor. Instead he took his place in London, far from the troubled East-End near affluent Notting Hill Gate. He lived among colonial Jews like Sir Ernest Oppenheimer of De Beers Diamonds, just a minute’s walk from the St Petersburgh Place Synagogue.

Public tributes to Nathan were rarely preserved but the New Zealand Mail wrote of him in an article in 1907, just five-years before his death. It was, in effect, a eulogy:

“He held the view a man may do his duty as a citizen most worthily, in some [cases], by working much and talking little. In his days of vigour he was a man of deeds … New Zealand was in the making and Wellington [came] into her own … Mr Nathan gave his time, his energy, his brain and his money freely to the practical side of politics.” And, perhaps echoing Nathan’s own suspicions about politics, it went on to speak of Nathan’s contribution saying: “On a fair estimate, one strong man working zealously and unselfishly for a country’s cause is worthy of twenty average politicians.”

At his death, Nathan left a template for a company that now had to continue without its patriarch into a new beginning. Nathan had contributed greatly to the colonial development and infrastructure of a nation, and laid the foundations of a company that would become known world-wide. Glaxo sales were set to boom and by 1918 they dominated company sales. By the end of World War II, the commercial legacy of Nathan’s endeavours – Glaxo – was known across five continents, its future assured.

![]()

References and Bibliography

Books and Written References

The New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs (1993). The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Volume II Bridget Williams Books, Wellington.

Davenport-Hines RPT and Slinn Judy, (1992). Glaxo

A History to 1962, University Press, Cambridge, Great Britain.

Millen, Julia (1991). Glaxo From Bonnie Babies to Better Medicines, Glaxo New Zealand Ltd.

Jephcott, Sir Harry, (1969). The First Fifty Years, Ipswich Press, Great Britain.

Internet References

Great leaps made under the Glaxo banner:

In 1919, the company employed the pharmacist, Harry Jephcott. He lifted quality control and developed Glaxo’s interest in pharmaceuticals.

Vitamin A and D were discovered in 1924. Vitamin deficiency disease such as rickets was common. The company launched its first pharmaceuticals.

The famous baby food to find a place on so many baby menus in New Zealand and Britain, Farex, was manufactured for the first time in 1934.

By the early 1930’s, power shifted from Nathan’s in New Zealand to London.

In 1935 the Glaxo Department became the company Glaxo Laboratories.

From 1946, Glaxo began experiments with, and helped develop, the world’s wonder drug, penicillin. For a time, it supplied most of the British market.

Around this time, the company began work on veterinary vaccines and products. In 1964 the revolutionary brucella abortus vaccine for cattle was produced.

In 1955, the energy and nutritional drink, Complan, was launched.

The first of the Glaxo mergers was completed in 1968 when Glaxo Laboratories in London joined with British Drug Houses (BDH).

The Bunnythorpe Factory was closed in 1974 but remains an historic building.

In 1996, Glaxo merged with Wellcome.

On December 27, 2000, Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham became GlaxoSmithKline, the world’s largest pharmaceutical company by market share at the time of merger.

WRITTEN BY DAVID PASSEY. David is a New Zealander living in Stockholm. He was a senior business journalist for the Sydney Morning Herald.

Jim Salinger And Hilda Nathan was my Great Aunt. She married into the Salinger family.

EXCELLENT AND MOST INTERESTING ARTICLE .

Its fascinating to read this. My Grandfather was the Company secretary of Joseph Nathan in the post WW1 period. I am afraid that I know very little about him other than his War Service, but if you have any details of his work for the company I would be very grateful to hear about then