New Zealand has long been heralded, mythologised (and of late, analysed) as a country that ‘rode to fortune on the sheep’s back’. The $4 billion+ export food industry of today might never have happened were it not for the innovation and wisdom shown by a group of legendary settlers of the 1880’s led by William Davidson and Thomas Brydone. The next time you carve into a tender fillet of Kiwi lamb sirloin, now exported to more than 190 countries around the world, you might like to chew on the fascinating story of how the frozen meat export industry began; a story of technology, determination, vision and pioneering colonialism.

In the 1870’s, New Zealand was a country of few people, exporting mostly wool and wheat. Other than the wool, most of the sheep was discarded: the meat was thrown away, or boiled up to make tallow for candles, as there was no way of exporting it, and too few residents to eat it.

Knight in icy armour

But this woolly profligacy was quickly to change as Brydone and Davidson siezed on a recent technology: refrigeration. As James Belch writes in Paradise Reforged, “from a purely technical perspective, refrigeration was the knight in icy armour that rode to the rescue of the New Zealand economy in the 1880s.”

William S. Davidson, born in Canada, of Scots parentage, became first a shepherd and later a businessman in New Zealand from 1865. He wrote of his regret at the waste of a good resource when he saw flocks of sheep being herded over cliffs, “knocked on the head and thrown down a precipice as a waste product”. Also involved in the early breeding of the New Zealand Corriedale sheep, he came to notice when he became the General Manager of the New Zealand and Australian Land Company in 1878. Described by some as, “a little too conceited and self-opinionated” he was also highly intelligent and energetic.

The wealthy NZ and Australian Land Company, a giant conglomerate of Scottish and antipodean money, owned many rich estates in the colonies. One of the most fertile was Totara Estate, nearly 15,000 acres of rich land, eight kilometres south of Oamaru in North Otago, not far from the Waitaki River. On its limestone soil grew some of the best wheat and potatoes in the world.

Thomas Brydone was the local manager for the company and a pioneer in the development of artificial manures, particularly lime. He has been described as “a well rounded manager” who could strike fear into hearts with his punctiliousness. He was known, for example, to become cross if there was jam on the breakfast table at Totara House rather than marmalade.

Davidson and Brydone began to discuss a frozen meat cargo to Britain in the early 1880’s. They were not alone; many people had noticed that Australia had successfully sent a cargo in 1880, while Argentina had achieved this some 5 years before that. But to send such a cargo from New Zealand would be to send frozen meat half way around the world – in a sailing ship, a voyage of more than 3 months. Many said it simply couldn’t be done.

Totara Estate

Vision stalled

But Davidson and Brydone planned that it would be done. Every detail was meticulously attended to, every obstacle overcome. Quality was their watchword. As David Murray, Chairman of the New Zealand and Australian Land Company later noted, Davidson had “…the genius for taking pains.” Brydone was responsible for building an export Slaughterhouse at Totara Estate and training six men as butchers, for 95% of the cargo would come from the Estate. He also arranged transport of carcasses, first by horse and cart from the farm to Totara railway siding, then by steam train (with iceboxes) to Port Chalmers. A steam-powered Bell-Coleman freezing plant was installed directly into their chartered ship, the “Dunedin”. They had about 600 carcasses frozen, when disaster struck – the plant failed. They simply sold off the meat or threw it away, had the plant fixed, and started again. Almost 5,000 carcasses were frozen on the ship over 2 months, and the cargo included pork, quail, rabbit and butter, although mutton was by far the largest commodity.

“Dunedin” sails

On 15 February 1882, the “Dunedin” sailed. Many of the passengers had cancelled their voyage, as they were afraid the crankshaft from the freezing plant would break and penetrate the hull. Others thought the plant would set the sails on fire. An interesting sidelight to the voyage was that the crew was delighted to have fresh meat every night for dinner – among the first in the world to do so. In the tropics, the “Dunedin” was becalmed and problems arose again. The cold air wasn’t circulating effectively around the carcasses. Captain Whitson, in charge of the “Dunedin’ on this historic voyage, crawled inside the plant and sawed extra holes. His quick action worked and he saved the meat, although he almost froze to death as the air began circulating better – crewmen had to tie a rope around his ankles, pull him out and resuscitate him.

Crew on board the “Mataura” in dry dock, Port Chalmers, Dunedin. The “Mataura took the second load of frozen meat from New Zealand in 1882

The cargo reached Smithfield markets in London three months after departure and every carcass – bar one – was in sweet condition. They fetched a good price, and immediately, many other companies began to charter ships, to get in on what proved to be a lucrative new industry. In 1882 the New Zealand Herald claimed that, “virtually, the exportation of frozen meat makes the colony of New Zealand as much a province of England, as easy a source of supply for the London market, as Yorkshire or Devon” – a claim that by 1922 would almost be a truism. What urged Davidson and Brydone to achieve the first cargo of frozen meat to a land 12000 miles away and from Britain’s farthest colony?

Turning a fine profit

It is hard not to conclude, after reading some of Davidson’s letters, that the good old motive of turning a fine profit, at a time when the wool prices were slumping, and the company was in some financial difficulty, was the spur. A massive and growing market was now available and one that didn’t require vast amounts of packaging, product innovation or marketing – all New Zealand had to do was maintain the quality of supply whilst increasing the quantity. No doubt their speed in getting the cargo sent was also increased by knowing that the Government was offering a 500 pound bonus for the first saleable 100 tons of meat to reach the UK – a bonus they subsequently received.

Looking inside a model of a ship displaying refrigeration technology at the New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch, 1906-1907.

Wellington wharf workers moving meat carcasses, c.1925

The implications of the vision and work of Davidson and Brydone are immense. They did not invent mechanized refrigeration (their technology was borrowed from overseas pioneers, notably in Australia), but they did utilize its potential more quickly, comprehensively and effectively than its inventors. Not only did their work, in unison with a transformation of New Zealand production, and distribution chains and demand in Britain, create a new export industry for NZ, and hundreds of thousands of new jobs over the next 120 years, but the structure of NZ agriculture and peoples’ lifestyles would be profoundly changed. No longer did there need to be enormous land estates, often owned by rich absentee landlords – there could be and would be hundreds of smaller family farms, able to prosper on both wool and meat.

Gear Meat Company label, Wellington, from a scrapbook of labels from 1880’s-1890’s

Protein from paradise

Their success also had an impact on Great Britain. Those first cargoes of quality, nutritious NZ lamb and mutton were eagerly received by a people in the throes of the Industrial Revolution, with cities, particularly London, hungry for such product. It had an impact on the health of the nation, especially up to the First World War. By 1933 New Zealand provided roughly half of Britain’s imports of lamb, mutton, cheese and butter combined. A number of reasons are suggested for New Zealand’s pre-eminent success in protein export, a success particularly impressive in relation to the size of its population. Among them are: ‘imperial preference’; the quality of New Zealand frozen meat (“New Zealand appears to have made a more precise and effective adaptation to the desires of the British market and to have achieved a substantial edge in perceived quality.” Belich, Paradise Reforged , p.67); and New Zealand’s figuring (and marketing of itself) as a rural, idealised, “Better Britain”. Whatever, the development of the industry coaxed by Davidson and Drydone’s desire, was historically significant, as Belich writes:

“From progress to protein was clearly one of the great transformations of New Zealand history. The New Zealand-British protein industry was fully-fledged by the 1890’s; crucial by the 1900s; became dominant in World War One; and remained so to the 1970s.”

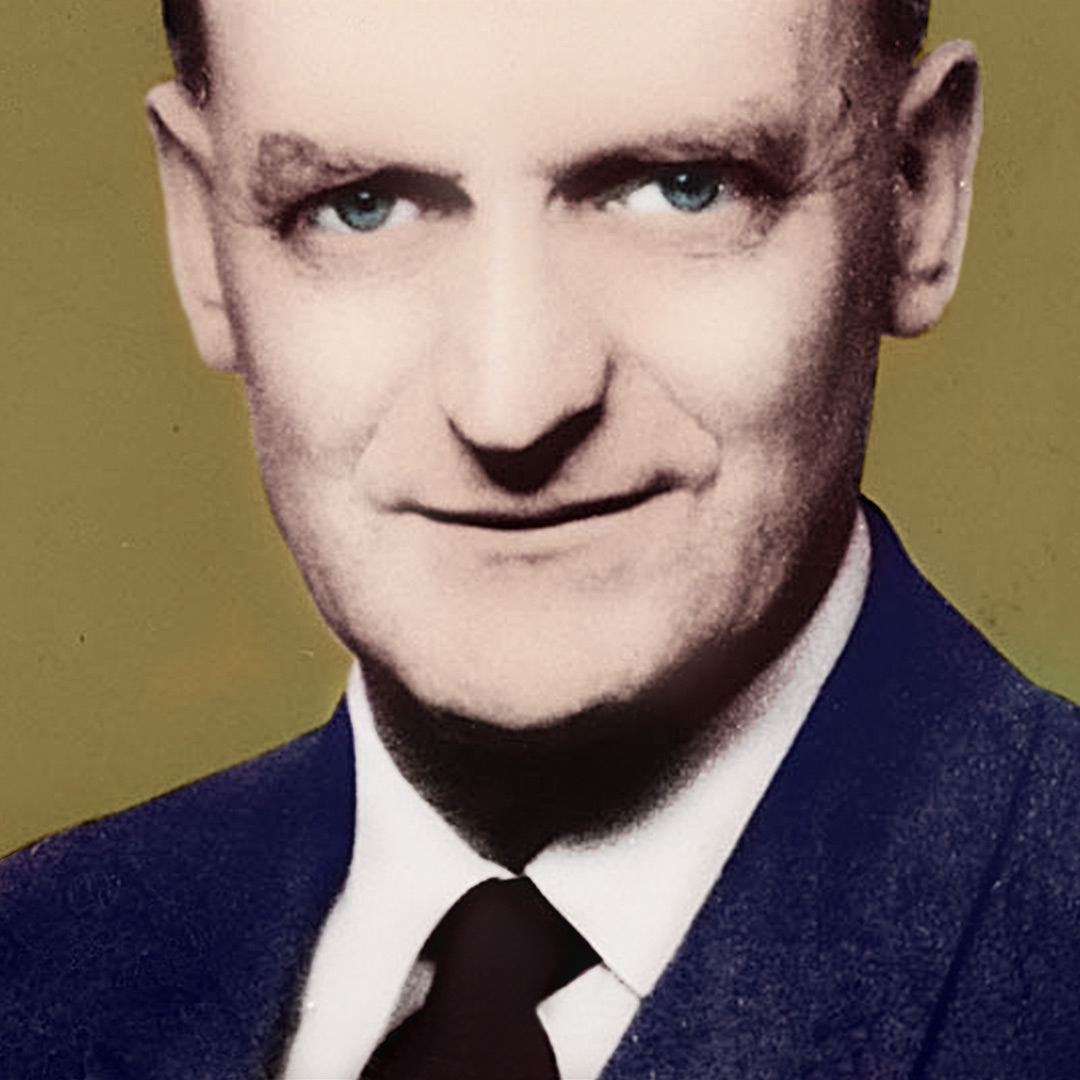

In the museum displays at the Totara Estate you can see the mutton-chop whiskered faces of William Davidson and Thomas Brydone, serious and Victorian, aware perhaps of their important place in the history of New Zealand. Among our first entrepreneurs, their ingenuity, and triumph over trial and travail saw the birth of what remain New Zealand’s two largest export industries – dairy and meat.

Display of frozen export meat carcasses outside the British New Zealand Frozen Meat Company, Christchurch, c.1900-1920.

For more information:

Totara Estate:

Today, you can visit the birthplace of New Zealand’s export meat industry. Totara Estate , owned and managed by the NZ Historic Places Trust, has proudly restored several buildings, including the Men’s Quarters, Stables, Barn and Carcass Shed. There are many displays, and in 2002, funds have been raised from the meat and port industries to build a life-size model of the original Slaughterhouse (which had fallen down some years ago) and to make a video about the history and development of the industry. You can visit the Totara Estate any day between December and March, or Wednesdays to Sundays between April and November (10am to 4pm).

Cuff, Martine. Totara Estate. NZHPT, 1982, reprinted 2002. Available by mail order ($15 incl p&p) or $10 at the Estate.

Or search the NZ Historic Places Trust Register.

For further biographical information on Brydone and Davidson visit the excellent online Dictionary of New Zealand Biography :

For wider historical context of the development of the New Zealand protein industry see:

Belich, James (2001) Paradise Reforged , Penguin, Auckland.

Davidson and Brydone were joint recipents of a Special IPENZ Millennium Award for “Shipment of Frozen Meat to the United Kingdom. Captain John Wilson, William Soltau Davidson and Thomas Brydone: for their fordightedness and dedication in taking the new technology of refrigeration and making it sufficiently reliable and efficient to enable New Zealand to develop an industry based on the export of frozen foods to the markets of the Northern Hemisphere.”

Pictures note:

Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library , National Library of New Zealand , Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of the images featured on this page.