Economics has a reputation for being a boring topic but the life and career of New Zealand born economist A W H Phillips was anything but boring. Engineer, crocodile hunter, innovator and war hero; Phillips traversed an unconventional path to become one of the most influential economists of all time. Such was his influence on modern economics, most major textbooks have a portion devoted to the concept named in his honour – the Phillips Curve. His paper on wage inflation and unemployment is the most cited macroeconomics title of the 20th Century and his pioneering work in the field of applied macroeconomics continues to influence modern economic policy.

An Innovative Childhood

Alban William Housego Phillips was born on the 18th of November 1914 at Te Rehunga – a small farming community near the town of Dannevirke, New Zealand (and just over 40 miles from Pongaroa where Nobel Prize winning physicist and molecular biologist Maurice Wilkins was born in 1916). More commonly known as Bill, he was the second youngest of six children born to Harold and Edith Phillips. His father was a notable Jersey cow breeder and his mother was a teacher at the local primary school. They lived in a modest home which was built by Harold and extended periodically to accommodate subsequent generations of family. As noted by Bill’s younger sister Carol, the Phillips household was “well rounded” – a quality cultivated by their father’s resourcefulness.

Harold Phillips also built a flush-toilet, a number of dams and a fairly sophisticated electrical system which was powered by a homemade waterwheel. The latter provided electricity for lighting as well as for the family’s American-made washing machine, the first of its type in the community. These innovations were undertaken at a time when there was no electricity or flush toilets in the region and when travel was still being undertaken by horse and cart. Indeed, the Phillips children travelled to school every day on the back of a milk cart and then had to endure an arduous, one hour bike ride along a jagged shingle road.

The Phillips Family. Bill is seated in the front row to the right of his father, Harold Phillips. Image used with permission from the niece of A.W.H Phillips.

Bill was just fifteen years of age when he began displaying his father’s innovative traits. He moved into a sleep-out and similarly wired it for electrical lighting; an old truck that others said could not be fixed was made roadworthy again; and exhibiting the sort of helpfulness that would become a hallmark of his adult character, he began driving children to school too. His sister Carol recalled watching Bill painstakingly repairing the truck; “learning the mechanics of the engine as he worked.”

The pick-up truck and electrical lighting were not his only childhood innovations. He and his brother developed a keen interest in photography, which led to them setting up their own darkroom and dabbling in a crude form of cinematography. They also became interested in radios at a time when electrical technology was still in its infancy. They built a number of radios and Bill was able to hone his ability as a technician – a skill that he would later make good use of during the war.

Having graduated from Dannevirke High School at age fifteen but too young and impoverished to enter university, Bill made good use of his childhood passions. He took up an electrical apprenticeship at the Tuai hydro-electric station in the Hawkes Bay and subsidised his meagre income by establishing the community’s first cinema. According to his sister Carol, cinematography almost became his fulltime career. Its popularity spread to other rural communities, resulting in the setting up of two more cinemas which Bill travelled between by motorbike, all the while maintaining his apprenticeship at Tuai.

The Tuai Hydro-electric station on Lake Waikaremoana, Hawkes Bay © Phil Rickerby.

The Big OE

Bill left Tuai in 1935 and embarked on what is often considered a rite of passage by many young New Zealanders. The Big O.E or Overseas Experience nearly always started in Australia and so it did for Bill Phillips. With little more than a knapsack on his back and a few dollars in his pocket, he spent the next two years travelling across Australia doing a variety of jobs including electrical work, cinematography, crocodile hunting and gold mining. This was just the first part of a ten year journey that would not only test his resourcefulness but also his will to live.

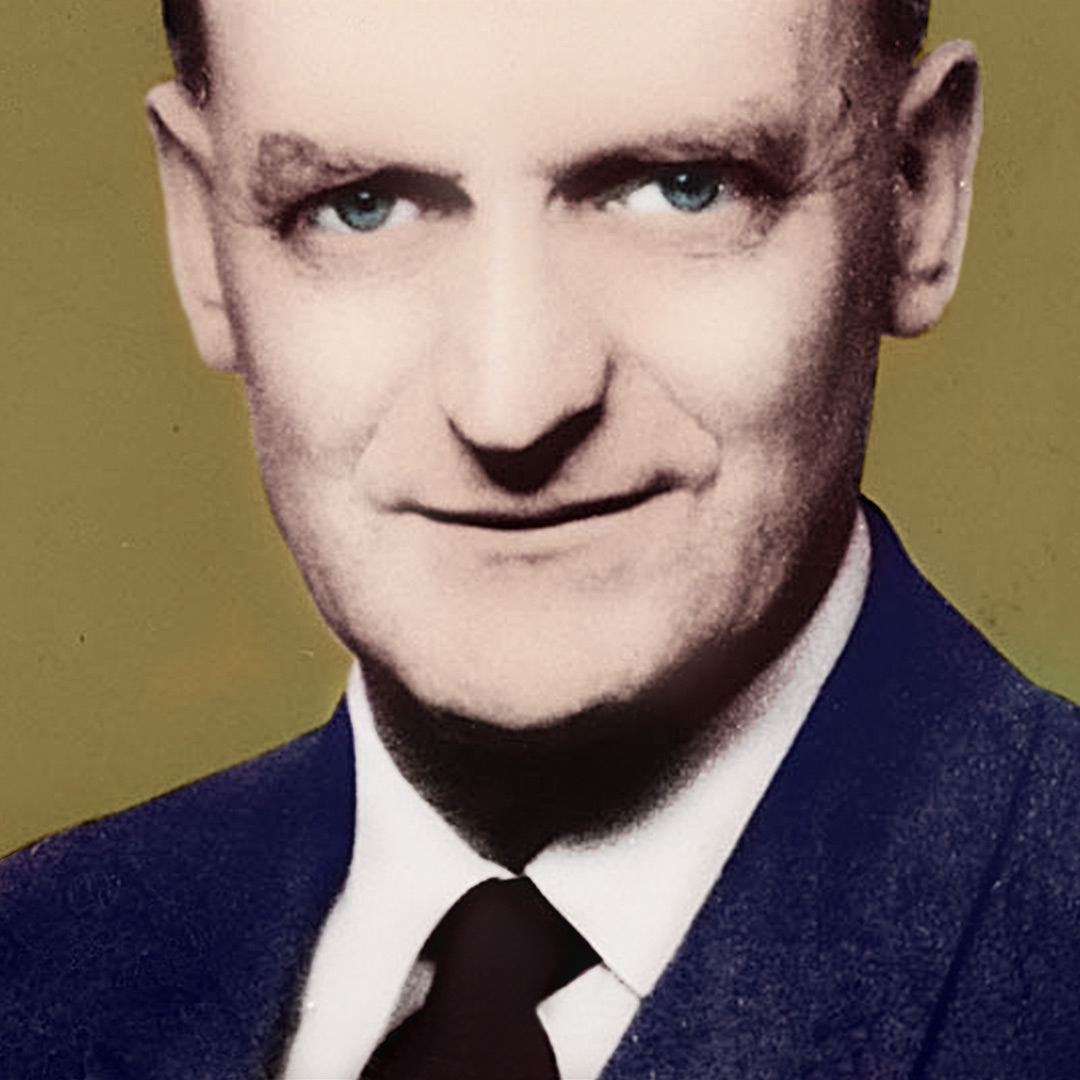

The young Bill Phillips, prior to leaving New Zealand for Australia. Image used with permission from the niece of A.W.H Phillips.

Struck by wanderlust and a desire to work in Russia, Bill left Australia in 1937 on a Japanese vessel bound for China. His plan was to get a mining job in Russia and gradually work his way to Britain. But just a few days into the voyage, Japan declared war on China and the vessel he was travelling on was diverted to Tokyo. Unaware that the Japanese were about to wage war in the Pacific, Bill unwittingly drew attention to himself by snapping photos of Japanese soldiers on parade. He was subsequently arrested in Horrishma where he was interrogated and accused of being a foreign spy. How he managed to wriggle out of this dilemma is unknown but according to a friend, “he got off lightly” and eventually made it to Russia via the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Bill’s plan to find a mining job in Russia also proved futile due to what he described as “a plentiful supply of political prisoners”. So the young New Zealander proceeded to London where he took up board with a Russian couple. Prior to leaving Australia he had been studying electrical engineering by correspondence and on arriving in London he was able to take up work in this field. Little is known about his time in London, other than he took up part-time study and also became a fluent speaker of Russian courtesy of the Russian couple.

“The Gifted Young New Zealand Officer”

Bill had spent little more than a year in London when World War Two broke out and having already acquired a taste for adventure, he wasted no time in volunteering his services to the Royal Air Force. It was therefore with some irony that they sent him back around the world to Singapore, where he was appointed Flying Officer to 243 Squadron. However, Bill also worked closely with New Zealand Airforce Squadrons 283 and 488. It is an understatement to say that these squadrons had been slapped together at the last minute. They were tasked with defending Singapore against a Japanese invasion but the American-made planes they had inherited were in very poor condition.

New Zealand Air Force pilots of No. 488 Squadron (Singapore 1942) scramble to get their American-made fighter planes airborne ©www.nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. This image has been reproduced with the permission of the Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

The poor state of these aircrafts was not overlooked by Bill who immediately went about trying to fix the ones that were not yet airworthy. In particular, he began modifying their guns. As recalled by his sister Carol; “His work on the necessary modifications was to retime the setting and firing of the guns”. Unfortunately, he was still working on them when the Japanese launched their attack. According to Carol; “It was not until the last two days before the fall of Singapore that he was able to get these planes operational and ready to fly again – too late.”

So on the 11th of February 1942, Bill found himself on the British cargo ship Empire Star as it prepared to leave Singapore for Indonesia with more than 2000 evacuees on board. Singapore was about to fall and there was now a desperate need to evacuate all military and civilian personnel. The Empire Star however, had barely left port when it came under fire by more than fifty Japanese aircraft. The vessel was not fitted with guns but one particularly innovative individual, thought to be an Australian, fixed a large gun to the deck of the ship and began firing at the Japanese. As it turned out, this individual was Bill Phillips:

“He mounted an un-mounted machine-gun, quickly improvised a successful mounting, and operated the gun from the boat deck with outstanding courage, for the whole period of the attack, which lasted for 3 ½ hours. Even when a section of the deck from which he was operating was hit by a bomb F/O Phillips continued to set an example of coolness, steadfastness and fearlessness.”

Australian and New Zealand Military personnel being evacuated from Singapore on the Empire Star ©Angell Productions http://www.angellpro.com.au/Hamilton.htm

The Empire Star eventually made it to Indonesia but this was not the end of Bill’s South East Asian escapades. Soon after setting up base on the island of Sumatra, he and his ground crew were on the run again – this time on foot with Japanese paratroopers in pursuit. Initially they were able to avoid capture by hiding in a makeshift camp but they desperately needed to leave the island and with this in mind, Bill came up with an audacious plan – they would build a raft from an abandoned bus and sail it to Australia! The Japanese, however, found their camp before they had a chance to attempt the risky feat and Bill was subsequently imprisoned as retold by his sister Carol:

“One day Bill and boat-working friend were returning to camp and saw their camp-minding friend’s head come into view. They promptly called to him, only to be dismayed by seeing a shorter Japanese figure on either side of him… they turned, and made a mad dash towards and over a sea cliff. This he picturised as a Walt Disney Character with his feet still running as he fell. The two men stayed at large a few days longer but eventually had to concede defeat and became prisoners.

Although Bill was a prisoner of war for more than three years he rarely spoke about the ordeal. He not only had a tendency to minimise the horrors of imprisonment but also his own heroics. On one rare occasion he told an inquisitive colleague; “She [the POW camp] wasn’t too bad once you got used to her.” Likewise, it was not until nearly three decades later that “the gifted young New Zealand officer” mentioned in Lauren Van Der Post’s book, “The Night of the New Moon,” was identified as Bill Phillips. In a letter to a former prisoner who had been imprisoned with him, Van Der Post wrote about a secret radio that a New Zealander by the name of Phillips had made:

“The Phillips you came across is the Phillips who served us so gallantly in prison and who built and operated the only secret radio we had in prison. Phillips was one of the most singularly contained people I knew; quiet, true and without any trace of exhibitionism.”

It is said that Bill broke into the camp commander’s office and stole parts off an old telegraph machine to make the radio – an act that would have cost him his life had he been caught. He used the radio to receive transmissions from the outside world but this was not his only act of bravery. He also invented an electric tea maker to help relieve the suffering of his fellow prisoners. Van Der Post referred to it as a type of “immersion heater” that tapped into the prison-camp’s electrical system, thus making it possible to heat water for hot cuppas prior to bedtime;

“Thanks to Phillips invention, the whole camp could have a secret cup of tea before creeping to bed… The result was when some 2000 cups were suddenly brewed that the lights of the camp dimmed alarmingly. The Japanese were mystified by this dimming of the lights every night at about 10.00 pm.”

From War to Economics

Bill was repatriated with his family in New Zealand following Japan’s defeat but according to his sister Carol, “he was woefully thin” and quite unwell. He barely weighed forty-five kilos; was unable to eat an average sized meal; and had a permanent tremor which was particularly noticeable as he chain-smoked one cigarette after the next. Despite his poor health, Bill decided to take up an offer given to many former Commonwealth servicemen in those days – an opportunity to study at a British university.

It is said that Bill’s wartime experiences had cultivated in him an interest in human behaviour and in the winter of 1946 he began a degree in sociology at the London School of Economics. A good knowledge of economics was needed in order to study sociology in those days and by 1948, the last year of his undergraduate degree, he had developed a keen interest in it. Economics at the time was dominated by Keynesian theory – government intervention and fiscal policies designed to control the ebb and flow of money in the economy. It would seem absurd that a student who had barely finished his undergraduate degree could come up with a way of modelling such an economy, but that was exactly what Bill did.

The Phillips Machine

In the last year of his undergraduate degree, Bill wrote an economics paper entitled “Saving and Investment: Rate of Interest and Level of Income”. Despite his best efforts he could not get anyone at the London School of Economics to read it. So he showed it to a friend, Walter Newlyn, who had recently been appointed to a position in economics at Leeds University. By his own admission, Newlyn read very little of the paper but was struck by a diagram Bill had drawn. The diagram showed the workings of the British economy but it was presented in a way that was akin to a modern computer model. Of course, there were no computers capable of modelling an economy in the nineteen forties, but that did not stop Bill from building one.

From left: Bill Phillips, Mrs Phyllis Langley whose husband helped Bill construct the computer, and Walter Newlyn in 1949. Image from “A Few Hares to Chase: The Life and Economics of Bill Phillips” by Dr Alan Bollard. Auckland University Press, Auckland, New Zealand (2006)

With Newlyn’s help and funding from Leeds University, Bill created the world’s first computer-model of a country’s economy. The Monetary National Income Analogue Computer or MONIAC, as it came to be called, was not so much precursor to the digital computer but a reflection of Bill’s creative genius. In the absence of electronics and sophisticated graphics, Bill used hydraulics and coloured water. The water was pumped via transparent pipes in and out of reservoirs labelled “imports”, “exports”, “taxes”, “spending”, “savings” and ”investments”, thus depicting the circulation of money in the economy.

A.W.H “Bill” Phillips demonstrating his Monetary National Income Analogue Computer (MONIAC). Image used with permission from the London School of Economics.

Despite being a hydraulic computer, the MONIAC had some astonishing digital computer qualities. The flow of money-water through its reservoirs could be manipulated to simulate the effect of changes in economic inputs and outputs – income, consumption, taxes and expenditure. Additionally, there were two scrolls of paper at the top of the machine connected to floats that could trace lines up and down like a seismograph, thus recording the ebb and flow of economic activity in real time. In his book “Undercover Economist Strikes Back,” Tim Harford notes that the machine could solve nine differential equations simultaneously and that it would be years before digital computers could support models as complex as the MONIAC’s.

Bill was invited to demonstrate his machine at the London School of Economics Robins Seminar in 1949. It is said that the professors attending this seminar were sceptical and somewhat dismissive of Bill’s academic credentials. However, their snobbery soon gave way to astonishment as pink water began carousing through the machine’s pipes and reservoirs. Smoke in hand and pacing incessantly, Bill simultaneously delivered a rousing lecture on Keynesian theory which left the professors speechless and his future career in no doubt.

Tim Harford suggests that the professors attending the Robins Seminar might not have been so astonished had they known more about Bill’s background prior to the lecture. He writes that; “Perhaps they would have been less so [astounded] had they known more about Phillip’s unorthodox education – the differential equations he’d studied by correspondence course; the hydraulic engineering he’d learned as an apprentice; the mechanical scavenging and repurposing he’d picked up on the farm and perfected in the defence of Singapore… and of course his courage.”

Not surprisingly, the MONIAC came to be known as the “Philips Machine” and Bill was subsequently elevated to the position of assistant lecturer following the publishing of a journal article on it in 1950. Articles about the machine also appeared in numerous magazines, including the American magazine “Fortune” in 1952 and the British satirical “Punch” in 1953. Such was its popularity, versions of the MONIAC were purchased by a diverse range of universities and organisations – Manchester, Harvard, Oxford and Cambridge Universities, the Ford Motor Company and the Reserve Bank of Guatemala to name a few.

The MONIAC. © Fortune Magazine 1953

Pioneer of Applied Macroeconomics

Bill rose from assistant lecturer to senior lecturer in 1952 and was subsequently appointed professor of economics in 1958. However, this was no ordinary appointment. It was the Tooke Chair in Economic Science and statistics which had previously been held by economic giants David Ricardo and John Stuart Mills. Bill’s appointment was an acknowledgement of his pioneering work in the field of stabilisation policy and in particular, the application of statistics to the development of continuous time models. Also known as applied macroeconomics, it more simply involved using fiscal and monetary techniques to stabilise key economic factors – national income, inflation and unemployment. Robert Leeson has more recently pointed out that the work Bill undertook during this period continues to define the field of applied macroeconomics:

“For the last forty years, applied macroeconomics, in so far as it connects the instruments of fiscal, monetary and income policies to the objectives of inflation, unemployment and economic growth has, to a large extent, been a series of footnotes and extensions to the work of [New Zealander] A.W.H. ‘Bill’ Phillips.”

Predicting and measuring the likely effect of macroeconomic policy on key economic factors (econometrics) became a major part of Bill’s pioneering work. Economists at the time were restricted in what they could predict by a lack of mathematical models and formulas. Somewhat ingeniously, Bill circumvented this problem by adapting models and formulas borrowed from engineering. This adaptation was, as noted by Leeson; “a path breaking application of engineering… techniques to economic systems.” Understandably, Bill’s work did not escape the attention of his contemporaries in America, particularly Milton Friedman.

Friedman and his colleagues at the Chicago School of Economics were grappling with similar prediction problems and in March 1952, he sought Bill’s advice on how to “approximate expectations about future inflation.” It is said that they were sitting on a park bench in the middle of London when Bill took an envelope from his pocket and scribbled down his adaptive expectations formula. Ironically, this formula would later be credited to Friedman and used to critique Bill’s better known contribution to economics – the Phillips Curve.

As an aside, such was his reverence for Bill’s economic genius, Friedman tried to recruit him not once but twice in the space of just five years. In recognition of his contribution to applied macroeconomics, Friedman wrote to Phillips in 1955 and offered him a visiting position at the Chicago School of Economics:

“I only know how stimulating I would myself find it to have you around for a year; and I venture to believe that the change in environment might be stimulating to you as well… it could be a prologue to a number of different lines of work.”

Bill declined the offer but in 1960 Friedman tried to recruit him again. Once again Bill declined, pointing out that Chicago is; “a notable… centre of empirical research in economics” but perhaps not as theoretical as the London School. Friedman in his reply appeared to take exception; “Heaven preserve us if Chicago should not offer as hospitable an environment for theoretical as to empirical research and conversely”.

The Phillips Curve

Bill described it as “a wet weekend” in 1958 when he began comparing nearly one hundred years of British inflation and unemployment data. After plotting the data on a scatter graph, he was able to fit a curve to it which would later be named in his honour. The curve showed an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. Bill was initially reluctant to present his findings but after some persuasion by colleagues, he wrote a paper which he entitled; “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861 – 1957”.

The Phillips Curve: Moving up the curve, the percentage of unemployment decreases as the percentage of inflation increases and vice versa. Used with permission from www.economicsonline.co.uk

Just one day after Bill’s paper had been submitted for publishing, it appeared in the journal Economica – a record short time even in those days. Quoting Economica, economist Alan Sleeman notes that it is the most heavily cited macroeconomics title of the 20th century;

“Half a century ago, Economica published what its webpage claims is the most heavily cited macroeconomics title of the 20th century — the paper by [New Zealander] A. W. H. “Bill” Phillips that introduced the Phillips Curve.”

Bill’s article captured the imagination of economists all over the world and before long similar curves were developed for other countries. The curve was seen as a godsend by governments – macroeconomic policies could now be used to justify higher rates of inflation in return for lower rates of unemployment. Bill had never intended that the curve be interpreted in this way but as Leeson has pointed out, it soon became the cornerstone of applied macroeconomics;

“The idea of an inflation-unemployment trade-off derived from a glance at this Curve was ‘snatched’ at first by American Keynesians, and, in an extraordinarily brief period of time, it became the cornerstone of applied macroeconomics... the belief that on-going inflation would purchase sustainable reductions in unemployment.”

Picture ©Rom Economics.

From all accounts, Bill was not pleased with his article or the way in which the curve was being used. On one occasion he described his work as “a very crude attempt” and on another, as nothing more than “a quick and dirty job.” Colleague Charles Holt recalled that he was a bit embarrassed by the attention it was getting. Indeed, the curve had been named in his honour but a bigger source of embarrassment was the way in which it was being used to justify higher inflation. Having always advocated zero inflation, Bill stated rather pessimistically; “had I known what they would do with the graph, I would never have drawn it.”

An Expectations Revolution

By the late sixties, Bill’s pessimism may well have turned to despair as inflation and unemployment began to rise simultaneously – thus making a mockery of the trade-off depicted on the curve bearing his name. He was well aware of the problem, having warned policymakers some years earlier that economic outcomes; “depend on [people’s] expectations” and “system stability is a factor of different expectations concerning future price changes”. However, it was not Bill but Milton Friedman in his 1968 Presidential address who attacked the curve’s use and ironically, Bill’s article for neglecting expectations;

“Phillips wrote his article for a world in which everyone anticipated that nominal prices would be stable” Friedman said [but] “as soon as private agents adapt their expectations to new rates of price rises, the trade-off vanishes.”

Friedman however, had simply stated what was already apparent to Bill and many other economists. Artificially hiking the rate of inflation initially causes unemployment to decrease but it also creates an ‘expectation’ of having to pay more for goods and services. Over time, people ‘adapt’ to this expectation in a variety of ways. Workers, for example, negotiate higher wages whereas businesses respond by employing less people. This eventually causes unemployment to increase or as Friedman noted, return to its “natural rate.”

Friedman was widely commended for identifying the destabilising effects of expectations. However, Bill had already discussed the issue at some length in a paper written more than a decade earlier. He had also written about it in his doctoral thesis – soon after providing Friedman with the original formula for calculating it! Robert Leeson is more blunt in pointing out that; “the adaptive expectations formula used to undermine [the use] of the original Phillips curve was actually provided to Friedman by Phillips.”

Friedman was not the only economist to benefit from Bill’s formula. After returning from London in 1952, he gave the formula to his doctoral student, Philip Cagan. In a letter to Cagan, he pointed out that the formula could be developed and used to calculate other macroeconomic relationships; “It can be carried over to other variables as well and is likely to be important in fields other than money,” Friedman wrote. “I have already used it to estimate expected income as a determinant of consumption.”

What followed has been described by economist Daniel Kuehn as an “expectations revolution”. Cagan used the formula to predict hyperinflation, Edmond Phelps used it to develop an expectations augmented Phillips curve; John Muth was inspired by it to develop the concept of ‘rational expectations’; and Robert Lucas applied Muth’s concept to the Phillips curve. The formula aided the monetarist revolution and all of them, including Friedman, received Nobel prizes for their efforts. However, Cagan is the only one who gave Bill any credit for developing the original formula. He wrote in 1991; “I could not find a workable representation of the expected change in prices. Friedman happened to discuss the problem with Bill … [who] deserves credit for what later came to be called adaptive expectations.”

It is said that A.W.H “Bill” Phillips wrote his adaptive expectations formula (above) on an envelope for Milton Friedman, who then gave it to his doctoral student Phillip Cagan. Cagan still refers to is as “Phillip’s formula”. Picture © C. Williams.

The Phillips Curve Legacy

By the early 1970s, Bill’s adaptive expectations formula was being called the Friedman-Phelps formula and the curve bearing his name was being typecast as one of the main villains behind a worldwide pandemic of hyperinflation. The name Phillips had become synonymous with the curve’s misuse and in particular, the belief that higher inflation would result in lower unemployment. Leeson points out that in their eagerness to trade unemployment for inflation, Keynesian economists had unwittingly made Bill a hostage to fortune:

“Phillips’ zero inflation advocacy was replaced by the belief that ongoing inflation would purchase sustainable reductions in unemployment. Keynesian advocates… gave a hostage to fortune which Milton Friedman, and others, brilliantly exploited [using the very formula Bill had given them], thus facilitating the monetarist counter-revolution.”

Ironically, the Phillips Curve was not discarded by Friedman and other monetarists. Rather, it was amended to take account of factors affecting the trade-off over longer periods of time. Often referred to as the “Short-Run Phillips Curve,” it now depicts the trade-off over a series of shorter time periods, thereby avoiding the long-term effects of inflationary expectations, external price shocks and sudden increases or decreases in the quantity of money.

The basic principles underpinning the Phillips Curve have not changed and contemporary versions of it are no less popular than Bill’s original conception. Indeed, although it is no longer assumed that there is a simple trade-off between unemployment and inflation, the Phillips Curve still underpins most macroeconomic models. As noted by Donald Kohn, former Vice Chairman for the American Federal Reserve, most researchers and policymakers still use the Phillips curve;

“A model in the Phillips curve tradition remains at the core of how most academic researchers and policymakers — including this one — think about fluctuations in inflation.”

Similarly, the former head of America’s Central Bank, Ben Bernanke, noted that most econometric models are underpinned by a Phillips curve:

“To project core inflation at longer-term horizons, the staff consults a range of econometric models. Most of the models used are based on versions of the new Keynesian Phillips curve, which links inflation to inflation expectations, the extent of economic slack, and indicators of supply shocks.”

A Life of Helpful Pragmatism

From all accounts, Bill had never taken much interest in the curve or the controversy surrounding its use. A contemporary of Bill’s noted that in keeping with his engineering background; “he wanted to know how systems worked [and was] not much interested in the scholarship of the subject – who had said what, and when.” It is little wonder then, that he did not assert his claim to the formula which was instrumental in changing the face of modern economics. Nor did he object to Friedman and others using it to advance their own interests. It was simply not in Bill’s nature to put himself above others or to seek academic kudos.

In fact, by the time of Friedman’s 1968 presidential address, Bill had already taken up a position as Chair of Chinese studies at the Australian National University. It is said that he wanted to be nearer to home but it was no secret that he was passionate about all things Chinese, including that country’s culture and language. Economist David Laidler, who had been eating with him at a Chinese restaurant in Chicago, recalled how Bill suddenly started speaking to staff in Chinese;

“We went out to a Chinese restaurant after his lecture in Chicago… and to our surprise, Bill began to chat up the waiters in what sounded to us like fluent Cantonese. He told us that he had learnt the language as a prisoner of war.”

Pragmatism mixed with helpfulness was a reoccurring theme in Bill’s life. Indeed, he always seemed to have access to tools in the advent that something might need fixing. Megnad Desai, a colleague of Bill’s at the London School of Economics, remembers complaining in the corridor that the central heating in his office had broken. Bill immediately came to his aid with a screw-driver in hand and began fixing it;

“Bill’s office was near mine. He heard me and came to my office. He pulled out, much to my surprise, an electrician’s screw driver, opened up the thermostat in my office and fixed my heating.”

Similarly, the wife of economist Harry Johnson recalls Bill coming home with her husband to talk economics. She was in the midst of trying to get her washing machine to work and was somewhat frustrated. On this occasion too, Bill came to her aid with a screwdriver and started fixing it;

“They walked in on my frustration with the washer. I met a slight-statured, quiet man who modestly asked if he could help. He tried something with a screw driver which may have helped… and then went back to talking economics.”

The Return Home

It was while lecturing at the Australian National University that Bill suffered a debilitating stroke which abruptly ended his brilliant career. Bill and his family immediately moved back to New Zealand so that he could convalesce. However, against his doctor’s advice, he took up a part-time lectureship at Auckland University. On the fourth of March 1975, the day after his first lecture, Bill suffered another stroke and passed away. He was just sixty years of age.

Like so many great people, Bill’s tenure in this world was short but impactful. Most economists are aware of Bill Phillips and in particular, the famous or infamous curve named in his honour. But few people, including economists, are aware of the pioneering work that he undertook in the area of applied macroeconomics – the adaption of engineering models to economics; the advanced work he undertook in stabilisation policy and continuous time modelling; and of course his adaptive expectations formula which facilitated the monetarist counter revolution.

Bill’s obscurity was largely due to his modest nature, which meant that he had little if any desire to publish his work. But in the year 2000, a compendium of Bill’s work was published by Robert Leeson entitled; “A. W. H. Phillips: Collected Works in Contemporary Perspective”. The compendium includes previously unpublished papers, all attesting to an in-depth knowledge of economic systems and advanced mathematics which placed him well ahead of many contemporaries. In addition to outlining his empirical and theoretical contribution to economics, the compendium also presents an ongoing interpretation of Bill’s work by twenty-nine of the world’s most renowned economists. As noted by one; “He was… an unaffected, undemonstrative, commonsensical and versatile genius.”

Another intelligent and undemonstrative New Zealander, quietly going about its business.

It is beyond the scope of this short story to provide an in-depth account of Bill’s economic achievements. However, his achievements have more recently been published in a book by Dr Alan Bollard – former governor of the Reserve bank of New Zealand. Entitled; “A Few Hares to Chase: The Life and Economics of Bill Phillips,” Dr Bollard provides specific details of Bill’s pioneering feats, some of which are listed below. Bill proposed and pioneered:

- The first computer model of a country’s economy

- Control-theory work on economic stabilisation

- Stabilisation policy working rules

- Systems-dynamics work in economics

- The trade-off between unemployment and inflation

- Continuous time modelling

- The adaptive expectations formula

- The use of rational expectations

- The study of Chinese economics

- The use of fiscal, monetary and macro-financial policy tools to stabilise world economies (monetarist economics).

A New Zealand Archetype

In many respects, the life and character of Bill Phillips mirrors the traditional archetypical figure tucked away in the national psyche of many New Zealanders. Bill epitomised pragmatism in that time-worn phrase the “number eight wire” mentality. He was courageous and intelligent but also humble and like the country’s national symbol, he shied away from the limelight, going about his business without any great fuss or fanfare. Economist Rex Bergstrom sums up Bill Phillips in the flowing extract and this story’s final tribute to a New Zealander of outstanding qualities whose ideas and innovations have had a lasting effect on the world.

“New Zealanders are proud of Bill not only because of his achievements but because he was very much the kind of man they most admire. He was unpretentious and on the surface seemed to be an ordinary man and yet, he lived no ordinary life. He was a modest man but his modesty was based on innate self-confidence. He achieved greatness but without flamboyance and his reputation rested on what he did, not on any gift of self-advertisement. He was an eclectic, skilled with his hands as well as his brain and also enjoyed the finest in both Eastern and Western cultures. Finally and most important, for it is in line with the New Zealand worship of improvisation, he was an innovator.”

References

Bollard, Alan (2016). A Few Hares to Chase: The Life and Economics of Bill Phillips. Auckland University Press, Auckland, New Zealand

Ferhan M. Atici & Daniel C. Biles (2013) Dynamic Equations with Rational Expectations on Time Scales. IJRRAS 15 (1)

Friedman, M (1968). The Role of Monetary Policy. The American Economic Review. Volume LVIII March 1968 Number 1.

Gosh, C & A (2011). Macroeconomics. Eastern Economy Edition. PHI Learning Ltd, New Delhi, India.

Hall, T (1989). The Rotten Fruits of Economic Controls and the Rise from the Ashes, 1965-1989. University Press of America. Lanham, Bolder, New York, Toronto.

Harford, T (2005). The undercover economist strikes back: how to run – or ruin – an economy. Little, Brown and Company. Boston MA.

Haye, B (2011) Economics, Control Theory and the Phillips Machine. Algorithmic Social Sciences Research Unit. Discussion Paper Series 11 – 01

Huang, S (2013) Phillips Curve, the Misread and Mislead in Economics. Journal of Chinese Economics, 2013 Vol. 1, No. 1: pp 151-157. Barr, Nicholas (2004) Phillips, Alban William Housego (1914–1975), economist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://archive.is/jsM7l#selection-196.0-200.0

Ibbotson-Somerville, Carol (1994) As the Twig is Bent: Personal Thoughts, Memories and Reported Experiences of My Brother. Mimeo.

Koenig, E. Leeson, R. Khan, G (2012). The Taylor Rule and the Transformation of Monetary Policy. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, Stanford California.

Kuehn, D (2014). Expectations augmentation did not start with Friedman and Phelps. http://factsandotherstubbornthings.blogspot.co.nz/2014/08/the-history-of-economic-thought-is-not_4.html

Laidler, D (2000) Phillips in Retrospect. A Review Essay on A. W. H. Phillips, Collected Works in Contemporary Perspective edited by Robert Leeson, Cambridge U.K, Cambridge University Press, 2000. pp. 515 + xvii

Leeson, R (2000) A. W. H. Phillips: Collected Works in Contemporary Perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge United Kingdom.

Leeson, R. (1997). A. W. H. Phillips. In T. Cate (Ed), G. C. Harcourt, & D. C. Colander (Assoc Eds). An Encyclopaedia of Keynesian economics. Cheltenham, United Kingdom, Brookfield V.t: Edward Elgar.

Leeson, R., & Young, W. (2008). Mythical expectations. In R. Leeson (Ed). The anti-Keynesian tradition. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Quiggin, John (2010) Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk among Us. Princeton University Press. 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey.

Ravier, A. (2013). Dynamic Monetary Theory and the Phillips Curve with a Positive Slope. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 165–186

Sleeman, A. G. (2011) Retrospectives: The Phillips Curve: A Rushed Job? Journal of Economic Perspectives. Volume 25, Number 1. Pages 223-238.

Solow, R. Taylor, J. Mankiw, G (2009) Fifty Years of the Phillips Curve: A Dialogue on What We Have Learned. In Understanding Inflation and the Implications for Monetary Policy, Edited by Jeff Fuhrer, Yolanda K. Kodrzycki, Jane Sneddon Little and Giovanni P. Olivei. Published by MIT Press.

Rivot, S (2013). Keynes and Friedman on Laissez-Faire and Planning: ‘Where to Draw the Line? Routledge Studies in the History of Economics. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon.

Ryder, W (2009). A System Dynamics View of the Phillips Machine. http://www.systemdynamics.org/conferences/2009/proceed/papers/P1038.pdf

Schwarzer J (2013) Friedman’s Presidential Address: Its German Translations. University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany

Turnovsky, S (2008) Stabilization Theory and Policy: 50 Years after the Phillips Curve. Invited address to be presented at ESAM08 Conference, Markets and Models: Policy Frontiers in the A.W.H. Phillips Tradition, July 9-11, 2008, Wellington, New Zealand

Van Der Post, L (1970). The Night of the New Moon. Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London

![]() Tim Harford – Video – The Indiana Jones of Economics, Jan 23, 2013

Tim Harford – Video – The Indiana Jones of Economics, Jan 23, 2013

timharford.com/2013/01/the-indiana–jones-of-economics/

About C.J. WILLIAMS

Born in Hastings New Zealand, Craig moved with his family to Sydney Australia when he was 13 years of age. He attended high school in Sydney and later began a colourful working career, firstly as a shipping agent and then as a private investigator for a small company in Sydney’s Eastern suburbs. His experiences as an investigator generated in him an interest in human behaviour, which led to him studying sociology and psychology at Victoria University in the 1990s. After graduating from Victoria with a BA, BSc (Hons) and MSc in psychology, he took up work in the field of psychology, specialising in the design, development and implementation of behaviour change programmes.

Craig has also written Legends stories about the pioneering surgeons Harold Gillies and Archibald McIndoe, and guerilla warfare pioneer and legendary engineer Te Ruki Kawiti.

Thank you for putting this story together about Uncle Albun. The brilliant yet humble men of the Phillips family were and are all the same and it is with great pride that I read this and many laughs over the similarities between "Bill" and Dad

A truly amazing story. Worthy of a screenplay and film one feels but so much to pack in so perhaps a TV mini-series instead. Forget a remake of The Dam Busters Weta - here's a story worth making!