Social change activist and longtime NZEDGE columnist Denis O’Reilly weaves a multi-layered tale located on the social edge of Aotearoa. Last week I heard on RNZ a documentary interview with Rastaman Tigilau Ness http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/accessallareas/audio/201798994/tigilau-ness-unity-pacific.

His band Unity Pacific is about to release a new album called Blackbirder Dread.

As usual the brother was perceptive in his recount of issues of social justice and the impact of colonialism upon Pacific peoples – the “Blackbirder” in the album title refers to the heinous practice of press-ganging Pacific Island men into servitude and slavery upon sailing ships in the later part of the 19th century.

During the interview Tigi was kind and gentle in expression but unerringly sharp and direct in aim. I called to congratulate him on his korero and suggested he hook up with Man Brooker prize winning author Marlon James who this week will speak at the Auckland Writers Festival.

Over summer I read James’ “A Brief History of Seven Killings”. Its mainly set in Jamaica in 1976 and features many of the characters that Tigi and I mutually knew in real life.

I was in Kingston in 1977 and despite my familiarity with place and context and previous exposure to Jamaican patois I found the book a difficult read due to its style and structure – imagine Keri Hulme’s The Bone People mashed with James Joyce’s Ulysses.

One thing that sticks out to me from his story and from my daily experience is how some members of sub-communities exist in an almost parallel universe to the mainstream citizen. As extraordinary as the things that happened in Kingston Jamaica in 1976 might seem to be today in fact these realities continue unabated.

After Jamaican gang leader Dudus Coke was arrested in 2010 there was a spate of extra-judicial killings of youth at Tivoli gardens, (Back o Wall) Kingston, by Jamaican Government Forces. Actual numbers killed are unknown but it is said to be in scores. It was 1976 run again.

Jamaica has no monopoly on over-kill. Only last month in north Bronx New York there was a huge para-military style operation to counter youth gangs involving over 700 police officers. Even helicopters were used in a sweep on an apartment complex in what was described as the largest gang takedown ever. It was if a Jamaican garrison had been transplanted to mainland USA

Even here in Aotearoa, as we experience our second methamphetamine epidemic, there have been a series of murders and instances of people being “disappeared”, with media chat about the possibility of intergang warfare. Just mix it with fear of Muslims and we’ll soon have politicians and press morphing Kiwi gangsters into terrorist folk devils. Chillingly, in Auckland, a young man named Imran Patel – who was previously jailed for holding a large knife to a driver’s throat and threatening to kill him whilst yelling an Islamic exclamation – was convicted of having and distributing violent Isis- related videos. Another guy, Niroshan Nawarajan was convicted of possessing similar material. This is an age in which we are grappling worldwide with self-defeating fundamentalism and a crisis of meaning. Through poverty despair and alienation this anomie explodes in forms of violence, both purposeful and random. Do not think we are immune. The current undercurrent of violence in Auckland is an as yet un-politicised case in point. Today’s Dominion Post cites French Prime Minister Manuel Valls as saying “The radicalisation of part of our youth which is seduced by the idea of a deadly counter-society is, I believe, the most serious challenge we have faced since the Second World War”.

It brings to mind the words of the erudite professor Scott Atran who, in an RNZ interview http://www.radionz.co.nz/audio/player/201781678 (hey, have RNZ got their mojo back or what!) giving some context to recent events in France, Belgium, and Syria, noted the risk presented by the disaffected urban young and their propensity to become rebels with a cause. He notes that violence is a powerful defence mechanism and that there is a certain joy and gratification in revenge. Atran points out that 70% of French prisoners are Muslim. Petty criminals are over represented amongst suicide bombers. He suggests we need to empathise (as opposed to sympathise) with the alienated and calls on us all to positively motivate our young people. Atran says that intermittently human beings need a sense of transcendence and self-sacrifice and that’s what drives civilisation – get in then with the positive directionality before the counter social fills the void.

But in another city, another valley, another ghetto, another slum, another favela, another township, another intifada, another war, another birth somebody is singing redemption song as if the singer wrote it for no other reason for this sufferah to sing shout whisper weep bawl and scream right here right now.

A Brief History of Seven Killings:601

Last month community activist Roy Dunn died after a prolonged period of illness. Who was this person, Roy Dunn? I knew him as the national leader of the Mongrel Mob Notorious Chapter. Despite the fact that I come from a supposedly rival assembly I considered him perhaps as one of the best change agents in Aotearoa.

Some years ago in South Auckland there were a series of eight murders related to youth gangs. Despite vast investment elsewhere through Police and MSD it was eventually through the work of a team convened and led by Roy that the problem was ultimately resolved. He brought together gang leaders from across Auckland and enrolled them in a whanau-focussed response bordered by the axes of axes of mana (respect) and aroha (love).

His work with addiction recovery through Te Ara Tika Trust has also been radical and pioneering.

Although Roy has physically expired his ideas and example will live on and amplify because he was a revolutionary leader. I have been blessed in my life to meet many great people, great leaders, and I rank Roy amongst them.

After a lifestyle of crime and subsequent imprisonment (triggered I believe by the fact that as a child he was unilaterally taken away by the State and separated from his family) he had reflected on his own behaviours, evaluated himself, and set forth on a fresh trajectory of non-judgmental whanau development. There are people who are leaders through appointment or election, and there are people who lead. He was of the latter category, and thus people actively followed him.

Roy could see the big picture as well as the detail of a specific situation. He was both soft and hard: unrelenting and immovable when required, kind and forgiving in most circumstances. He was generous, and made himself available to others, even in poor health. In early March I met in Tauranga with him and his lieutenants, two community activists and a cop. We were seeking his advice on a programme of community action amongst gang whanau. We were given words of insight, of resilience, and of love. He provided powerful but actionable advice and we will apply it.

A week later he was down here in Hawke’s Bay encouraging his Mongrel Mob brotherhood to adopt positive “E Tu Whanau” values.

Roy has gone but his kaupapa lives. Ma whero ma pango ka oti ai te mahi. Red and black, we are in this together. Aue te tangi, aue te mamae o te ngakau i te hinganga o te toa! E Roy, kei te rere nga roimata ki a koe. Haere ki o taua matua tipuna. Haere ki te Po! Haere ki te Po! E te whanau pani, ka nui te aroha ki a koutou i tenei wa. E tangi! E tangi!

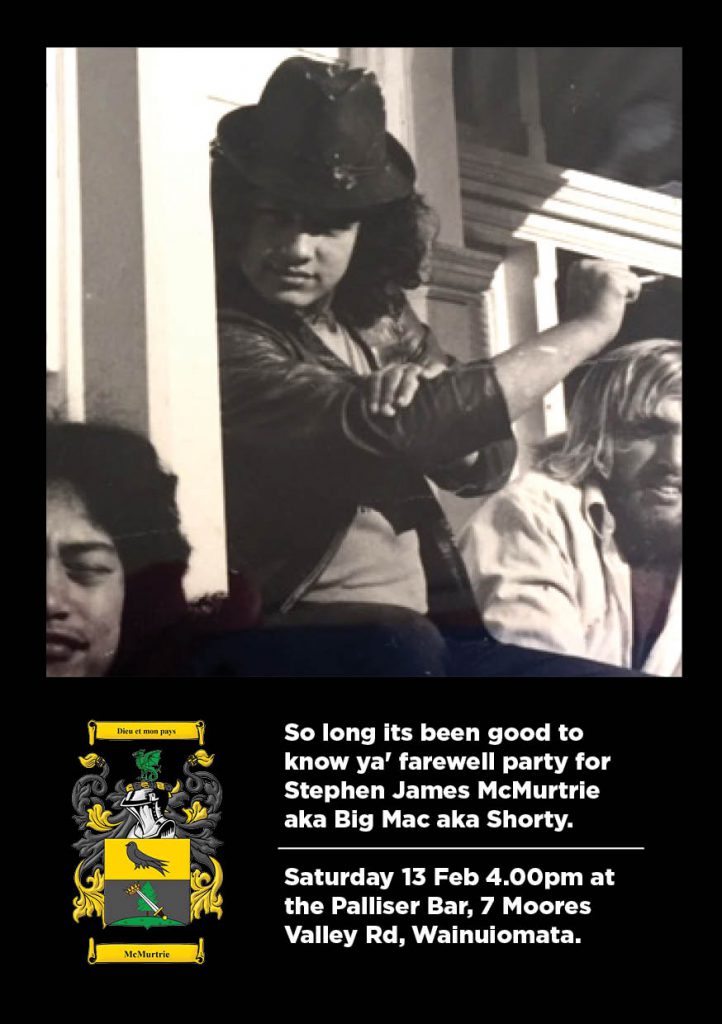

Just prior to Roy’s death another leading gangster – a member of the Nomads – also passed away. This was the man we knew as Shorty, aka Big Mack, Stephen James Mc Murtrie. As his health rapidly deteriorated he sent me a request to come and see him. I thought about what our conversation might consist of. There was little that he had done in the last 20 or so years of his life that I agreed with and I anticipated that we would end up having a cynical and somewhat counterproductive korero. But my kinder angels spoke to me and reminded me of 1974 when Shorty was only about 15 years of age and still quite innocent. He was part of my extended whanau and came with us on the Storm and Friends Tour of the north island complete with rock band and theatre troupe – as it was the way in those days.

I decided to see if we could get members of the band together and hold a farewell gig. It became so.

Horace Mahauriki got the musos together, Ross France flew down from Auckland, Taape, Koha, Garry Crawford and my son Tareha and I drove down from Hawke’s Bay and various senior Black Power members and Shorty’s Nomad brothers all gathered. Brannigan Kaa started us off with some old school party songs and Maori ballads, then Horace and his boys took over. Even Shorty had a solo on the guitar.

I brought a couple of hundred bucks of fish and chips and between Ross and me the bar tab was kept going. The bros knew I did not condone Shorty’s activities but also saw that we accepted him as a member of our extended whanau and embraced him with unconditional aroha. It was a sublime evening.

Gangster to the end about a fortnight before his eventual demise had his face fully tattooed with a skull-head design. Freaky. Moreover he insisted that he be buried sitting up. And so he was. He eschewed the undertaker and instead was treated with traditional Maori preparatory burial methods. He was washed and oiled and wrapped in a cocoon of woven flax and then was seated upright in a specially made chair. When it came time for his departure from home to cemetery the Highway 61 provided a huge V8 stationwagon as a hearse. The 61 members used their bikes to block the motorway on ramps so the funeral procession drove unhindered by traffic. It was quite a sight.

There would be people arriving home to tell their family “You won’t believe this Do you know what I just saw on the way home? I swear it looked like a body in a chair on the back of a ute”.

We gathered for the burial at the Taita Lawn Cemetery and as is my way – and expected role – I gave a poroporoaki and read the following excerpt from Colm Toibin’s The Testament of Mary by way of scripture.

He gathered around him, I said, a group of misfits, who were only children like himself, or men without fathers, or men who could not look a woman in the eye. Men who were seen smiling to themselves, or who had grown old when they were still young. Not one of you was normal, I said. Yes, misfits, I said. My son gathered misfits, although, he himself, despite everything, was not a misfit, he could have done anything, he could have been quiet even, he had that capacity also, the one that is the rarest, he could have spent time alone with ease, he could look at a woman as though she were his equal, and he was grateful, good-mannered, intelligent. And he used all of it, I said, so he could lead a group of men who trusted him from place to place. I have no time for misfits I said, but if you put two of you together you will get not only foolishness and the usual cruelty but you will also get a desperate need for something else. Gather together misfits I said, and you will get anything at all – fearlessness, ambition, anything – and before it dissolves or it grows, it will lead to what I saw and what I live with now.

Colm Toibin (2014) The Testament of Mary New York. Scribner: 6

So that’s the two deaths, and with Toibin’s words in mind now we will segue into the single killing:

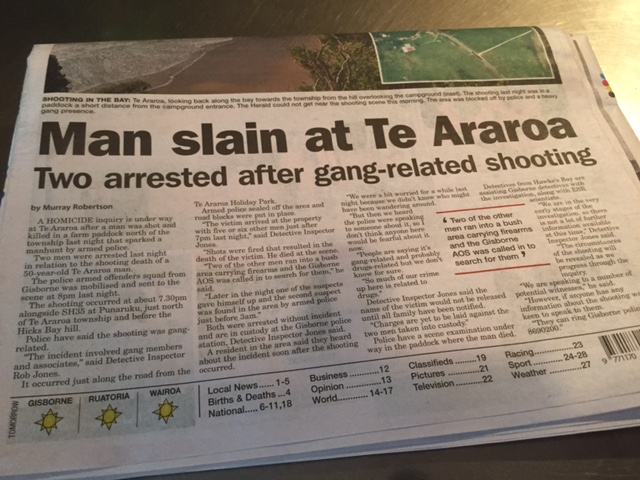

In the second week of February 2015 I got a call from Nath. “Bro, bro”, he said, (and then, did I hear a sob?) “bro D, Tumanako’s been killed, he’s been shot at Te Araroa”. I breathed out. News of death comes always as a shock, yet it is an inevitable consequence of our birth. In Tumanako Tauhore’s case, even within the specific context of being shot dead, I was not surprised. The chances of his death in violent circumstances had been high since about 1979. I was however nonplussed. What had happened? Tumanako was the key Black Power president on the East Coast. He was staunchly anti-meth. Was this a result of the actions of a force external to the Black Power or was this an internecine thing? Either circumstance was possible. I figured I should get to Te Araroa asap.

As I’d initially heard it Tumanako had been ambushed by two guys and shot dead in front of his 4 year old daughter and 16 year old step-daughter. It was apparently a result of a somewhat trivial dispute arising from an instance of what might be called domestic violence. Tumanako had made it clear that he would “sort out” the perpetrator and fear had set in to this man’s mind.

But when fear sets in things can get well out of control and this is what happened at Te Araroa. The perpetrator “Willy G” sought refuge with a mate and his family and the fear escalated when they learned that Tumanako had several of his chapter members in town. They saw one and one and interpreted it as eleven. They imagined they were all going to get the bash and, to be fair, Willy G was certainly due for a hiding from Tumanako. Several calls were made to the police seeking help. None was forthcoming. The two guys armed themselves and waited for what they anticipated as an inevitable visit.

According to the version of events given to me Tumanako had brought his men to Te Araroa to help clean up his marae for his namesake uncle’s tangi. After their work was completed they went for a swim. On the way home Tumanako had apparently spotted Willy G’s car at a house on Te Araoa Rd. He had his four year old daughter in the car with him. He spun around, got out and started to walk across the paddock to the house. Some of his boys started to follow him. He was barefooted and unarmed. In panic and fear Willy G and his mate opened fire and cut him down.

As you might imagine the local media saw it as a gang matter and initially speculated that drugs were involved as well. Neither was true. It was a family matter. Just about all of those involved were related to each other, some quite closely.

There was a cop at the gate guiding the crime scene. I was standing there somewhat dazed, meditative even, and the cop said the strangest thing to me. He said “I feel sorry for these two boys” – meaning the shooters. “What do you mean?” I asked incredulously. “Well” he said “they were protecting their home and family from gang members”.

The forces of the law had treated Tumanako pretty harshly during the course of his life, and it seemed there would be no reprieve or succour in his death. It might be fairly said that the Gisborne Police did not pursue the case with the same vigour and eye for detail if the boot had been on the other foot, that is, if Tumanako had shot someone dead.

The matter came to trial in February of this year. Lawyers joke about a “Gisborne Jury”, generally white and highly conservative. The defence lawyers took the line of defence offered by the cop at the crime scene – that the shooters were defending family and home from a group of gang members intent on doing them harm.

The Crown prosecutor, Steve Manning, who I thought did a good job with a poor hand, cut to the chase. He proposed to the jury that if it was simply a case of two seemingly good men killing a purportedly bad man then why even bother with a trial? Indeed.

The Gisborne Jury delivered a not guilty verdict and they both walked free, not even the option of manslaughter being declared.

But it was during the trial that the reality of the point that I made earlier in this story, that there are quite distinct sub-communities co-existing in our land, was confirmed in the evidence and the dialogue of examination and cross examination. The record reads like a piece lifted straight out of Marlon James. Here’s a slightly edited version of the evidence in examination and cross-examination given by Tumanako’s right hand man Joe “Black” Davoren:

Examination:

Q. Now Mr Davoren did you have any affiliation with a gang?

A. Yes.

Q. Which one?

A. Mangu Kaha Aotearoa.

Q. Black Power?

A. We’re all whānau with the fist, yeah.

Q. Tumanako Tauhore. You obviously knew him, how long at the time of his death, how long had you known him?

A. Maybe three, yeah three years. Just three years?

Q. So tell us how it was that you came to know him?

A. Well when I moved back home I had, I had no chapter to go with, brotherhood. He came round, got to know me we got to know each other and he got to know all my kids. They look at him as a uncle. I looked at him as a leader, a father, a brother.

Q. And as a consequence of that what happened?

A. He asked me to jump on to his chapter and I did.

Q. Now Tumanako at that time what was his role within Mangu Kaha?

A. He was our captain, our priest, our leader.

Q. And for you personally what did you gain from belonging to Mangu Kaha?

A. Oh just what everyone likes, a loving whānau, yeah without the whānau structure you ain’t gonna get nowhere in this world.

Q. And so within that structure what sort of things did you do?

A. Exactly what I said, family things. Build the, you build the club up for all the family to enjoy days out, barbecues, go out fishing, the odd hunt here and there, yeah or just have days with the family just kick back and yeah and when I say family Mangu Kaha.

Q. Now did your group have – well you tell us about how you’d dress if you’re all together with your group?

A. Just like any club, club uniforms, yeah.

Q. What did you call it?

A. Colours.

Q. And what were the colours, describe them for us?

A. Oh a leather jacket.

Q. Yes.

A. Mangu Kaha Aotearoa with a fist.

Q. Did you have one of them?

A. Yes.

Q. Now if we can now please Mr Davoren turn to a different topic and I want to ask you about the day before Tumanako was shot so it’s the Sunday, the Sunday the 15th of February. Where were you that day?

A. On the Sunday yeah I was at work.

Q. Can you tell us please how you got up to Te Araroa?

A. The rangatira picked us up, picked me up.

Q. And the rangatira you refer to as who?

A. Tumanako.

Q. And did you know that he was coming through to pick you up?

A. No.

Q. You didn’t know?

A. No.

Q. Now were there any other vehicles with him or just him and his –

A. No it was just, just the bro.

Q. Now obviously you didn’t know he was coming you’ve told us that. Did Tumanako say why he wanted you to come up to Te Araroa?

A. No.

Q. Did you ask him?

A. You never ask a person in, in command.

Q. In what sorry?

A. You never ask a person in command.

Q. How were you dressed, what were you wearing?

A. My, my t-shirt and my, my jacket my korowai. And gumboots and denim shorts.

Q. And the t-shirt had what on it?

A. Mangu Kaha Aotearoa.

Q. When Tumanako approached the house how was he moving?

A. Casual.

Q. Did he have anything in his hands?

A. No.

Q. And again at this point did you know what he was doing?

A. No.

Q. What did you do when you saw him heading over there?

A. Oh like any solider would do, follow their captain.

Q. Now at that point did Tumanako the way he was moving change?

A. Yeah actually it did, it did change.

Q. How did it change?

A. Oh he got into a bit of a hurry.

Q. A hurry yes and so how fast was he moving now?

A. Oh just a quick walk.

Q. How far behind him were you?

A. It would’ve been about 250 metres behind him.

Q. And how fast were you moving?

A. Like I said, casual.

Q. Did that change?

A. No. But it changed – it changed on one, on one fact.

Q. What was that?

A. When we heard firearms.

Q. The firearm shots that you heard, the first firearm shots you heard, could you tell what direction they may have been coming from?

A. Up in the trees. In behind those Puriri trees.

Q. And the person in behind the Puriri trees what was he holding?

A. Rifle.

Q. Did you recognise that person?

A. No.

Q. Male or female?

A. Male.

Q. Māori, Pākehā?

A. Māori.

Q. And when you saw that person was that person saying anything?

A. Telling us to fuck off.

Q. At that point what, if anything, did Tumanako do at the point that the shots were being fired?

A. He was looking around.

Q. Now how many shots do you think you heard at about this point?

A. At about that point yeah, nah, nah, it was, ah, was too many to count.

Q. Were they spread over time or quick succession, how, describe –

A. Repetitive action, not like it’s a semi-automatic but yeah it was repetitive action.

Q. And could you tell where the bullets were going?

A. Everywhere.

Q. In relation to where you were where –

A. Yes it was more or less aimed at the bro.

Q. The bro being?

A. Tumanako.

Q. How could you tell that?

A. Oh we could hear it whistling.

Q. Now the people that were with you or behind you, did they, what did they do, do you recall?

A. Oh we carried on walking, yeah, until –

Q. Until what?

A. Well another rifle come out.

Q. Well let’s talk about that now. Did you see another rifle come out? – what was it that you saw?

A. A high calibre rifle.

Q. And was it being held by someone?

A. Yes.

Q. And what was that person doing with the rifle at that point?

A. Aiming.

Q. How could you tell they were aiming?

A. I’ve done a fair bit of hunting in my time.

Q. Describe the position of the person?

A. Standing position, leaning on the, leaning on the side of the house to steady the rifle, anyone knows you’re gonna, if you’re, if you’re gonna lean on the side of, the side of anything you’re, you’re stabilising the shot.

Q. So leaning on the side of the house?

A. Looking down the barrel, through the scope.

Q. In what direction?

A. Towards the Rangatira.

Q. Tumanako?

A. Yes.

Q. Now when you saw the second gun, and the second person, what was the next thing that happened?

A. Yeah, round was squeezed off. To the sound for me sounded like a 3-0, or large calibre. The smallest it woulda been woulda been 270, but either, either, it’s still a big gun.

Q. So in contrast to the shots you’d heard first how much bigger? How much louder?

A. Oh heaps louder.

Q. And once you heard that shot fired can you tell us what you saw happened to Tumanako?

A. He fell to the ground.

Q. Did he get up again?

A. No.

Q. What did you do at that point?

A. I got his daughter outta there.

Q. Well we’ll come to that, but immediately where you were in the paddock what did you do when you saw Tumanako go down.

A. Yeah like said, my first instincts were once I heard that and seen the bro go down my first instincts was to get her outta there.

Q. Okay. So presumably you had to leave the paddock –

A. Yes.

Q. To get to the car? So tell us about that, what did you do? Did you – how did you move?

A. Got up straight to the, straight to our girl, told the bro’s to get her outta there, take her home.

Q. Now as that was happening did you hear any other gunshots?

A. Yeah, 22 was still going.

Q. Could you hear anything being said from anyone?

A. Yeah same thing, telling us to fuck off. The bros all had taken cover and I was still trying to get through the gate just to get to the bro.

Q. Did you know what had happened to him? Silly question but if you can confirm what you believed had happened to him?

A. Yeah, yeah he’d been shot.

Q. Now in the end what did you decide to do given what was happening?

A. Well after the third loud shot eh and not being able to get in there, well the bros were telling me to get in the car and go. I didn’t wanna leave him. Tumanako, a fallen brother.

Cross Examination:

Q. Mr Davoren if you can’t understand my question please tell me. Yes.

Q. You had this lovely swim with your group, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And issued with your colours by your leader, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And that’s what having colours means to you isn’t it? It’s an affirmation that you’ll follow your leader?

A. I would’ve followed him with or without colours.

Q. But having colours is a statement to the world that you’ll follow your leader?

A. Yeah like I said, I would follow him with or without colours. You follow the man that leads you. It’s like the rugby team. Your captain, your captain goes somewhere you follow him.

Q. Blindly?

A. It doesn’t matter, you’re still there with him. That’s what loyalty does to a person. Family.

Q. That wasn’t my question Mr Davoren and you know what my question is. Having colours is a statement to the world that you’ll follow your leader?

A. Yes.

Q. What right did you have to go onto the property at 4819 Te Araroa Road?

A. My bro, like I said I was just following my leader.

Q. What right did you have to go on that property?

A. No right.

Q. No right. But why did your leader have to go onto that property?

A. His family and his stepdaughter was in there.

Q. But they were yelling out to him to go away weren’t they?

A. Not that I could hear.

Q. Not that you could hear. Well why did you have to follow your leader on the property if he was merely going to his family, step-daughter? When someone tells you to f-off the property isn’t that a direction you should leave?

A. Not if you got a fallen comrade.

Q. This was before you had a fallen comrade. You told us in your evidence that someone’s yelling out f-off. Isn’t that a command for you to leave the property?

A. Yes.

Q. Why didn’t you leave?

A. ‘Cos I was following my leader.

Q. Regardless?

A. Yes.

Q. Because you would’ve followed him come hell or high water wouldn’t you?

A. Yes.

Q. And you’d have done what he was going to do come hell or high water?

A. Depends on what he was gonna do.

Q. And nothing would’ve stopped you, would it?

A. Yes.

Q. What would’ve stopped you?

A. For me to be lying right beside him.

“Gather together misfits I said, and you will get anything at all – fearlessness, ambition, anything – and before it dissolves or it grows, it will lead to what I saw and what I live with now” Toibin

Epilogue